I have always had an odd fascination with the title of a particular Kazuo Ishiguro book — “The Remains of The Day”. For reasons that have not yet arranged themselves into coherence in my head yet, my association with that specific assembly of words has always been with music. Music, for artists, and listeners, will always be the remains of our days — the only artifact of times bygone which stays luminous in our hands, when the grief has lost its bite, and the joy has faded into warmth — something that has a lifespan that we can happily allow to outlast ours.

There is an odd joy I feel inclined to derive every single time I am a little too late to an album, when an extremely thin film of dust has settled on it perhaps — the momentum has slowed slightly, there is more leeway to feel like you have made a discovery, walked into a space an artist has perhaps moved forward from, evolved, changed, while you stand and feel its walls, wide-eyed. All this to say, I listened to Adi and Suhail’s 2014 album, Culture Code Landscape on my bus ride home and felt a lump in my throat and then smiled all the way through on my walk from the bus stop.

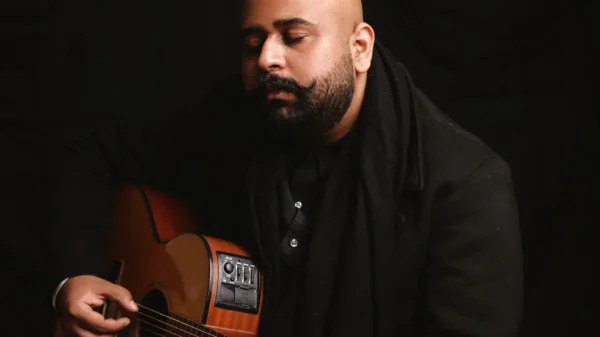

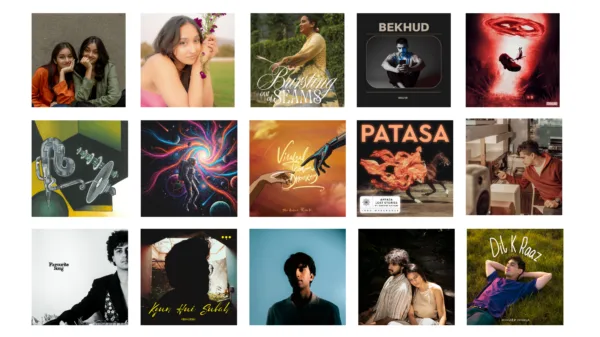

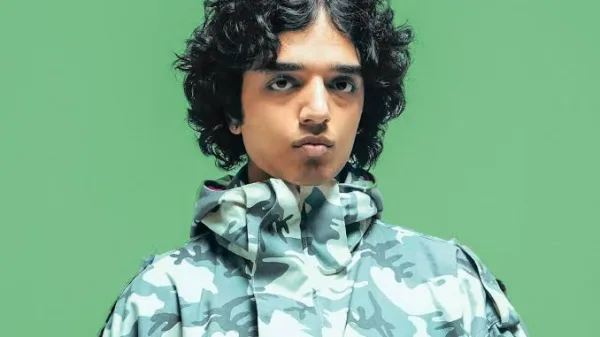

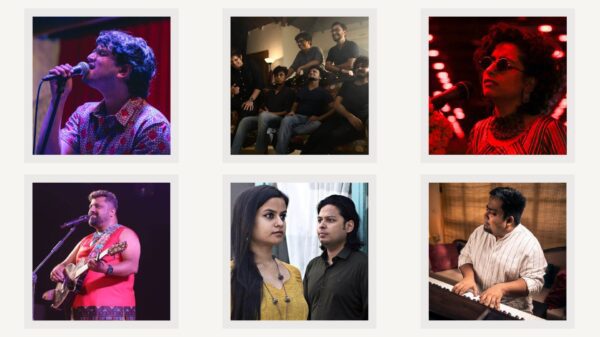

Adi and Suhail — or Aditya Balani and Suhail Yusuf Khan are an interesting combination. A multifaceted guitarist, composer, producer and wearer of multiple musical hats, Balani meets Khan, a sarangi instrumentalist and vocalist, known widely for being invaluable to groups like Advaita, Yorkston/Thorne/Khan, and Khamira. Culture Code Landscape is a synthesis of their respective styles, combining distinct sonic identities into a wonderfully enmeshed tracklist. Naina, the first track from the 9 on the album, is an adaptation of Baba Bulle Shah, and an incredible situating of the iconic early 18th century Punjabi poet into a track that assembles electronica and the sarangi simultaneously into moments of singularity and combination. In an interview with Shahin Bhatti, Khan says, “I clearly remember that lazy afternoon. I was fasting because it was the holy month of Ramzan. Adi was comfortably sitting in his practice room with his favourite Fender strat on his lap strumming some really epic-sounding chords. I entered the room, greeted him and started singing this poem written by Baba Bulle Shah and the song Naina was born. We both felt this aura of massive energy surrounding both of us and that was the day I think we decided that we should seriously take this to another level,” — that energy gains an almost tangible quality on the track. The outro, with Balani’s guitar, followed by Khan’s sarangi paired with Isaac Haselkorn’s drums cements a quality of grandeur to the devotional yearning on it.

Dil Tere, a Punjabi folk song, with additional lyrics from Suhail Yusuf Khan, is one of the most fun songs on the album. A stunning synth and sarangi arrangement forms one of the most intriguing parts of the song. By now, one has familiarised themselves with the earnestness and light, wind-like tonality that Khan’s voice possesses, one that renders the lines “mera mujhme kuch bhi nahi / jo laage so tohra hai” a believability, that the self-surrender feels only natural, the most plausible order of things for the artist to choose for himself.

NH7 has a video on YouTube, which has Aditya and Tarun Balani on guitar and drums, and Khan on the sarangi, playing Zindagi. It is supposed to be a recording of them performing the song, and also to create a music video of the same. The visuals are a time capsule, switching between heavy block-like frames, filters and color gradings that one associates with the early 2010s YouTube videos. The handheld camera flips extremely quickly between all the players, and that is how the instrumentalisation also works, with the drums, Balani’s incredible segment of a solo, Khan’s sarangi, all tied together by the latter’s vocals. Khan’s lyricism is commendable, as he whips out lines like “yeh ganga teerath kya hai jab maile se mann ko saaf na kiya” and “kyu shor badh paya hai sukoon main kaisa tumne mahaul kiya” with ease.

Laage Re is perhaps one of the most popular tracks off the album, and for good reason. Moreso than anything that is said on the track, Khan’s crescendoing sarangi cuts through your chest as he calls “aaja naa jaa, main waree, tope jaaoon jee / aaja gar-a, main waaree, tope jaaoon jee”. There are very few fusion albums out there which get the absolute relinquishing in any form of love derived from sufi music right, but this one gets it. There is a tear-inducing element to how the sarangi quells on this one, “a tug at the heartstrings”, as someone [me] going for a more cliched expression would say. Qalandar is another brilliant track, with the lively syncopation of the drum beats adapting the arrangement of a gradually quickening dance routine.

The album ends with a reprise of Zindagi, sung by Shilpa Rao. Rao’s clear vocals accompanied by Tomos Williams’ trumpet is much simpler a soundscape than the ones that precede it. However, I think it is an appropriate curtain drawer, there is a dream-like element to the singer’s delivery, and the trumpet is almost mystical, wistful — first separate and then interspersing to form the sonic equivalent of looking up at the sky in a more vacant stretch of a city road. Perhaps that is why the album art features an open sky and a deconstructed architectural space, or maybe that is only my interpretation — but then, maybe that is the purpose of music, to interpret, reinterpret, encode meanings to a body of work, and somehow it all turns into questioning the many trials and tribulations of life and its incomprehensibilities in song form — after all, these are the remains of our days, held in firm and shaky hands.