In the last decade, India’s independent music scene has grown rapidly, driven by streaming platforms, social media, and a generation of artists eager to create music outside the Bollywood space. Yet, despite its creative energy, the Indian indie scene remains fragmented, loosely organized, and limited in its global visibility. Meanwhile, other non-Western music industries like South Korea’s K Pop and Latin America’s Spanish-language pop have turned their local sounds into global cultural powerhouses. Their success offers lessons that go far beyond choreography or catchy reggaeton rhythms. It is about structure, strategy, and identity; areas where Indian indie still has much to learn.

South Korea’s music industry, for example, has built a carefully organized system that transforms local talent into international icons. The K Pop economy was valued at around five billion dollars in 2022, driven by exports, concerts, and merchandise. Groups such as BTS and BLACKPINK are not only musicians; they are cultural brands supported by production companies that invest deeply in training, storytelling, and fan engagement. Every stage of an artist’s journey, from vocal coaching and choreography to their public persona, is carefully shaped. While this approach may seem overly commercial, it demonstrates an ecosystem that treats music as both an art form and a complete cultural product.

In India, indie music often thrives on raw talent and passion but lacks this kind of structural support. Many independent artists handle their own promotion, visuals, and branding while balancing other jobs to sustain themselves. What the scene needs is a stronger framework for artist development, including mentorship programs, smaller training labels, and government-supported initiatives. Such systems could help musicians build long-term careers instead of relying on one viral song for recognition.

Another key lesson from K Pop is its global first mindset. Korean entertainment companies never viewed their domestic audience as the final goal. Since the late 2000s, they have produced multilingual content, collaborated with international artists, and ensured that all material is accessible with subtitles for global viewers. This approach helped K Pop connect with audiences far beyond Asia. By contrast, Indian indie music often stops at the national level. Artists tend to focus either on the English-speaking urban audience or the Hindi-dominant market, overlooking the power of regional languages and international reach. A Tamil or Assamese indie act could just as easily attract global listeners if their music were supported by strong storytelling, subtitles, and high-quality visuals.

The Latin music industry provides another model worth studying. In 2024, Latin music revenues in the United States reached 1.42 billion dollars, representing more than eight percent of the total recorded music market. Most of those hits, from artists such as Bad Bunny, Karol G, and Rosalia, are sung entirely in Spanish. They show that language does not limit success when the sound is authentic, innovative, and well-produced. For Indian indie musicians working in a country rich with regional languages, this is an inspiring example. Instead of chasing Western templates or English lyrics, Indian artists could embrace regional identity as their greatest export.

Streaming has also been central to the Latin music explosion. In Latin America, about eighty-eight percent of recorded music revenue now comes from streaming. Platforms and algorithms have allowed local musicians to reach international audiences without depending on traditional record labels. India already has a large digital audience, but what it lacks is the strategic understanding needed to turn streams into long-lasting fan communities.

The strongest lesson from both K Pop and Latin music, however, lies in fan culture. K Pop thrives because of organized fan groups that promote albums, stream songs in large numbers, and purchase merchandise. Latin artists, too, have built emotionally loyal fan bases that feel deeply connected to their stories. In India, fandom still revolves more around film stars than musicians. Indie artists would benefit from cultivating smaller but dedicated fan circles through regular engagement, such as live sessions, behind-the-scenes content, and interactive events. A small group of committed listeners can often achieve more than a large but passive audience.

Production quality is another area that sets these industries apart. K Pop and Latin music videos are known for their cinematic visuals and creative storytelling. Indian indie musicians, limited by budgets, often produce simpler videos that struggle to stand out online. Yet visuals today are inseparable from music. Investing in direction, design, and conceptual storytelling can elevate a song from being simply good to being memorable and culturally significant.

However, adopting these lessons does not mean copying foreign models. India’s context is very different. The K Pop trainee system, for example, depends on intense discipline and control, which would clash with the independent and experimental spirit of Indian indie musicians. Likewise, the Latin industry’s close ties to the United States market give it advantages India does not have. The most valuable takeaway for Indian indie lies in the core principles of long-term vision, collaborative practice, professional production quality, and a globally oriented mindset, each reimagined within the Indian cultural and economic context.

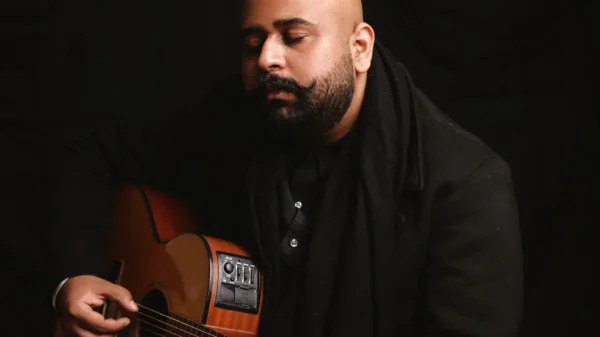

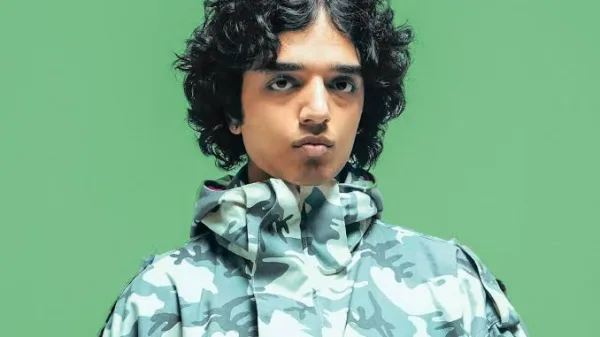

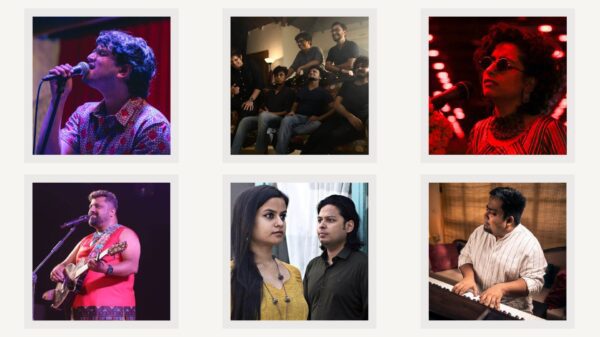

At its core, the Indian indie movement already possesses what international audiences often seek: emotional depth, cultural diversity, and sincerity. From the intimate songwriting of Prateek Kuhad to the multilingual energy of When Chai Met Toast, Indian indie artists already express distinct identities that could travel globally. We should also acknowledge acts like PCRC (Peter Cat Recording Co.), W.I.S.H, and Outstation, who represent different but equally important possibilities within the indie landscape. PCRC has built a unique identity through their fusion of retro jazz, cabaret-style theatrics, and existential lyricism, creating an audio-visual universe that feels both nostalgic and avant-garde, the kind of world-building that international audiences find memorable. W.I.S.H, meanwhile, leans into dreamy electronic textures, synth-pop sensibilities, and soft-focus aesthetics, proving that India can produce alt-pop that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with global acts while still feeling emotionally rooted in local experiences. Outstation brings a completely different strength to the table: a raw, regionally grounded alt-rock and folk-inspired sound that captures the lived realities of young Indians outside the metro bubble. Their music reflects a cultural honesty that could easily resonate beyond borders if given the right visibility and support. What the industry now needs is structure; a combination of K Pop’s precision and Latin music’s cultural confidence. This means better artist development, cross-regional partnerships, and a clear global vision.

If Indian indie learns anything from Seoul and Sao Paulo, it should be that global success comes from authenticity, not imitation. Both K Pop and Latin music rose to power by embracing their own languages and identities. When Indian indie stops trying to sound Western and begins to sound proudly and recognizably Indian and presents that sound to the world with skill and ambition, it will no longer be just a local movement. It will become a global voice.