In art and in life alike, exposure is a notion more political than one might usually consider. To be acknowledged, accorded, and finally, hopefully, accepted, one needs to be seen. One does not need John Berger either to know how political seeing is too, when what gets to be seen is determined by social forces, the gravity and ramifications of whose reality often elude the mainstream public imagination. In other words, to have oneself be acknowledged, knowingly or unknowingly of the repercussions, they must inevitably descend (or ascend, depending on how you choose to look at it) into the realm of performance. And social performance, inevitably, is an arena with a deliberate cruelty in how—and indeed, who—it rewards.

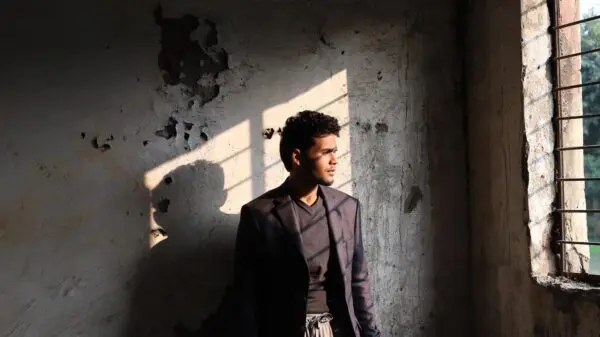

I first came across Gogol’s music back in college when he still used to go by Amartya Ghosh, in a period which was for me marked with voracious consumption—almost ingestively—of music. The Delhi-based musician’s Broken Compass had come out a couple of years ago, and the six-song album held me in part rapture, part stupor through many a balmy day. Gogol’s songwriting is, more often than not, redolent of a dalliance with dwindling, and yet his voice shines through with an honesty that is hard to come by in Indian indie. In the deep dive that I went into back in the day, Ghosh’s videos on YouTube spoke of a candour whose genuinity osmosed all the more potently because of his inhibition. Despite his many live performances in Delhi, it was apparent—at least at the time—that Ghosh’s favourite spot was not the proscenium. Away from the spotlight, the gaze and the clamour, his “Lone Dancer” found clemence in “dancing all alone” when the “curtains are down”, still “waiting to be seen”. Even when persuasive, in a song like “Lovebirds at Daybreak”, he chooses dawn—a time of day shrouded in silence, and consequently imbued with intimate privacy—and still, even with burgeoning longing, tenuously waits for his beloved to “call my name”.

“Verdict” first came along my way, nudged by the YouTube algorithm, courtesy of the aforementioned deep dive a year prior. In this video, Ghosh, like this writer, scrawny as ever, walks through the streets of Delhi presumably at dawn with just his guitar and a voice resonant enough to hold a very potent mnemonic space for the average Bengali listener, inducted into the rewaaz of morning vocalisation. The first glimpse I had of the song fashioned it as an aubade, and the bare (and barren) honesty on Ghosh’s face lends the song a profundity that lingers in the cavern it creates for itself. I have since grown to showing the song to those I have thought would appreciate it, facetiously introducing it as an “incel love song”, and always following it with the disclaimer that the description is less than half the truth of this song. Lyrically, indeed, the song deigns to self-pity, with Ghosh claiming himself to be “the sad one” on whom all the “pretty girls take pity”, and the deft alliteration stops short of masking how openly he is prepared to talk about how pathetic he finds himself. The song, personal as it is, dithers between such confessions and a dialogue to a (now lost) beloved, who tells him, piling on the misery, that “it’s over now”, and they “were never meant to be”. Out of the contexts of melody and Gogol’s obvious personhood, some of these lyrics might seem troubling; but within the aforementioned contexts, especially within the absolute lack of hypermasculinity I have witnessed in him in the years I have followed his music, inceldom is out of the question. What arrives instead is the kind of terrible beauty that could be borne only by nakedness, and it is fortunate that Gogol allows himself to undress.

After more than six years in the works, to the admitted adoration of mine (and many others’), Gogol has finally released “Verdict” in the form of a live rendition. The purity of the lament and the lack of grace are tempered—lifted, as it were—by the studio production, but they still, for better, ooze through the seams of the production. Accompanied by Jenn Steeves, the duo’s harmonies bring warmth to the forlorn lullaby, offering it the deserving portraiture it had been seeking for so long. In the almost eight long years since the release of Broken Compass, Ghosh has been hitherto, sadly, sporadic with his music. Freelancing is the tragic reality most independent artists have to face, which has for him resulted in releasing a handful of singles spread over a generous amount of time. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Ghosh released “Secret Life of Miserable People” as part of MAI Mixtape – Edition 1 on Bandcamp and “My Funny Quarantine”, and he has just had a stint at the growing Delhi boyband that goes by the name of Green Park. Having turned that corner, “Verdict” is the first of eight new songs Gogol has planned for release over this year. Time has matured him and though most of his new music should have the listener see a new side of his, the fact that “Verdict” survives means so does the defendant, and it augurs, albeit in familiar steps, a new dawn for the singer-songwriter.

(The writer oscillates between Amartya Ghosh and Gogol, contingent on the phase of the artist being talked about.)