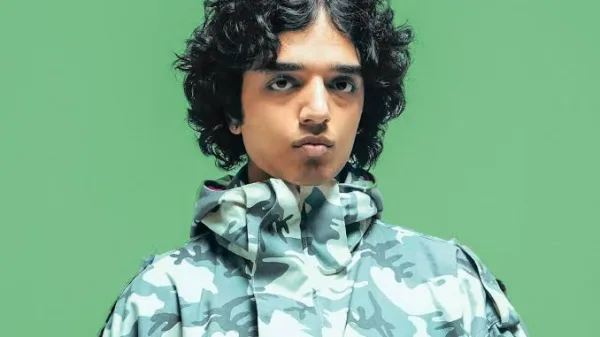

A few days ago, rapper Raga made a statement, one that sent all the grapevines of DHH listeners abuzz. Post the large-scale outrage against the Kolkata rape-murder case, and the media’s suddenly reawakened conscience leading to increased ‘reportage of violence (sexual and physical) directed at women — a number of artists in the Indian musical stratosphere decided to weigh in with their support. The rapper posted on his Instagram story, “Talking about my own songs which glorified/objectified women in a bad way. Aaj ke baad I condemn this kinda art poore sire se aur dil se.” This is a rare feat when it comes to desi hip-hop stars and starlets, who have mostly prided themselves relentlessly on whatever they have said through time, mostly taking offense to criticism, branding people too sensitive, or perhaps ignored it all together — even more so because of the artist’s everlong association with bars like “Le lenge jaan teri, haste haste raat bitaake.”

Discourse around misogyny within hip-hop is not new, a simple Google search leads to countless results popping up, and even our own cultural knowledge is enough to contextualize the subject with music from multiple artists, and one does not even have to dig too deep into the past, there are ample artists in recent public memory who have engaged in writing numbers that do not just dissolve women of their individual identities and frame them as functions necessary for the narrative, but also outright threaten violence. From Eminem to Kanye West, to most of the early work from Tyler The Creator, to icons like Dr. Dre. At this point in our understanding of rap and hip-hop music, I think we have come to accept misogyny as an ironic feature, or a sizable bitter pill — in favor of the musicality and the catchiness and the exclusive personal and social messaging. Mia Moody-Ramirez writes that, “Most female or woman artists define independence by mentioning elements of financial stability and sexuality. They denote that they are in control of their bodies and sexuality. Many male rappers pit the independent woman against the gold digger or rider narrative when they preach p in their lyrics. Bynoe noted that in the hipp-hop world, women are rarely the leader. Instead, they are usually depicted as riders, or women who are sexually and visually appealing and amenable to their mate’s infidelities. Conversely, a gold digger uses her physical attributes to manipulate men and to take their money.” (Wikipedia, Misogyny in Rap Music)

This brings us to desi hip-hop, and it becomes difficult to completely allocate it an identity that is definitive, and perhaps that is one of the best parts. One cannot deny how heavy its influences are, especially from American rappers in the music industry — while British drill occupies an incredibly respectable space in the culture at the moment, very little of it has seeped into mainstream rap music or the Indian counterpart of the ever elusive genre. One can easily notice the similarities, while most rappers acknowledge their influences, either situating them in the age of gangsta rap, the golden years of trap music, or deriving inspiration from the current host of mumble and psychedelic rap personnel — it is also notably present in the vocabularies of these artists. While AAVE exports like “dawg”, “shawty”, and “homie”, (and occasionally the n-word, hello, MC Stan) have permeated the lingo of rappers, [resulting in their chronically online younger audience adopting verbal cues, strengthening their lexicon into a synthesis of articulations from both the heroes of hip-hop from the West, to their much closer, more relatable, and highly accessible counterparts in their own country). However, Desi hip-hop, also is undeniably situated in questions of undeniable class, religious and political struggles that run deep into the bones of India, is intrinsically mired in questions of poverty and violence and derivatives of their own locations within the country. I think it is this extremely complicated contextualization of its components that gives Desi hip-hop its intriguing character, something that is so indubitably foreign yet so powerfully homegrown.

The misogyny problem is predictable, with its American roots and our own domestic, centuries-old brand of denigration of women, combining under the Indian umbrella of a male-dominated genre that often overlooks its female creatives or names the interest in the domineering women artistes as exceptions, and not entry-points or discernible breakthroughs, one can barely afford to be surprised. The problem has also seeped into, and solidified itself so well into the culture as a whole, that any attempt to point it out is usually met with dismissiveness or chagrin, and sometimes pleas to ignore the obvious and notice the artistry that went into crafting the work in question. What is obvious and ever present then transforms into a “side effect” of sorts, something that you have to overlook in order to enjoy the art in question.

I think every hip-hop fan, who identifies as a woman, is faced with a moral dilemma. It is a question of conscientious consumption. For a really long time, I have engaged with content deemed “crass” — half of my reasoning for my pursuit of the same has been my persistent distaste for the rich and their alignments with the pride in all things refined and pristine, and because it also provides for an area of intriguing research into displays and narrativizations of masculinities, femininities and expressions of sexuality, particularly those of brown bodies. During my time studying at the University of Delhi, I had attended shows of multiple DHH artists, standing in corners, rapping back the lyrics word for word, and felt the city open itself up to me through their voices and verses. When it came to things that would be deemed problematic, I told myself that I was trying not to take “things too seriously”, and that it was “all ironic”. However, over time, I have come to contemplate this logic that I have applied to myself. How much of it is taking things on surface value and how much of it, precisely, is just consolation offered to the self? Overtime, while reviewing albums that address issues of class, or meander into the territory of meme music (Gauntlet), I have, mostly given them the pass — tolerated and overlooked the blatant signs and semiotics of music that is drenched in perpetual distaste for women, creating space for the artist to cash in their irony/joke/it’s-not-that-deep pass. And yet, the question has bubbled and simmered within me consistently, does this assumption of irony count as complicity? The answer, of course, is yes.

The problem is as much the festering wound of culture, as it is of the artist as an individual. There almost seems to be an unenforced that follows female listeners of hip-hop, across borders. Amy DuBois Barnett, in For Black Women, the world of hip-hop has always been a minefield of misogyny writes : “Maybe we had also been too inculcated with hip-hop’s “no-snitching” code, a misbegotten form of self governance that shielded the community from external punishment within racist systems but enabled all manner of injustices to go unchecked. And then there’s the unspoken cultural oath that Black women have taken to protect Black men. Because Black women have watched how systemic racism in our society has turned Black men into targets, we are collectively reluctant to add t’o the burden they already face just walking down the street. So we often refuse to hold them accountable for problematic behaviors, even when the behavior is deeply misogynistic, even if it means minimizing the trauma of the survivors, even to save ourselves”– while the systemic racism is inapplicable to the circuits of Desi Hip-hop (casteism is prevalent in rap circles, unsurprisingly), the code of protection of female hip-hopheads is almost expected. One has to believe in the marginalization of desi rappers, no matter where they are located within society, and defend them and overlook their errors to be counted as a proper “hip-hophead” – forming a cult like circle of defenders who agree with every little heinous thing that you have done, branding others “snowflakes” and “dangers to the culture.”

There is this assumption that when one speaks of misogyny in desi hip-hop, it functions as a ban on desire of any kind — where sexuality comes under an oppressive ban and men (could you ever believe it) have to withdraw any form of expression of interest/attraction that they experience, and restrain themselves to eternal celibacy. The crux of this situation, as one finds oneself repeating over and over if one claims allegiance to feminism, is the approach to desire, and the disenfranchising of women from being active figures in a reciprocal dynamic —- instead allotting them the space of a silent yet seductive recipient, often represented directly in the form of video vixens, something that should have stayed a relic of the past.

Every once in a while, we come across a video in our Reels section that makes fun of Badshah and Honey Singh for their infamously creepy lyrics, early on in their career and strains of which are still present in their current music. As DHH becomes more mainstream, and starts occupying an important space in the public understanding of the Indian music industry, it becomes important for all of us, especially men, to develop a strong culture of critique. The onus, obviously, does not rest solely on women to construct a movement against DHH artists, who are essentially making music for a primarily male fanbase. While reposting slogans, and news headlines about rampant crimes against women, it also becomes necessary to be critical of the culture that one is part of. What has plagued me, constantly, is that it is not that DHH artists are unaware of the gravitas of misogynistic behavior — in fact, it becomes an element to threaten your adversary with (as exemplified by the SOS Seedhe Maut fiasco), a weapon to humiliate and expose your adversary with, and yet — when the time comes, little evidence is released to the public : it is almost as if predatory behavior can exist as a knife hanging over your neck, hinting at your imminent downfall, but an industry-wide bro-code prevents one from “snitching” — because of course, the crime itself is of little value to the players in question.

This also, does not mean that we are advocating for an immediate boycott/cancellation of rap artists — because shunning someone from music circles barely does anything, it reduces a culture-wide problem into an individual-specific issue that can be handled if the problematic elements in question are removed / replaced. Instead, we do need to develop a restorative process of critique where there is a scrutiny of all that they decide to release into the world as music. Not every song needs to be a 3 minute robotic “We Love Women ! We Support Women !” anthem, (because one, that would barely seem believable considering the trajectories of the artists in question, and two, we have enough corporate jingles for feminine hygiene products), instead what one insists for is humanisation of women in lyrics, which should be the bare minimum.

I think it is time, with the rapidly multiplying and expanding reach of DHH artists, we take a step or two away from moving like an impenetrable cult which forms a defense network around their favorite artists, and instead prioritize artistry. Over the last decade, these creatives have managed to establish a burgeoning section of the music industry and most of it has been the product of the labor of independent artists, who have put their blood and sweat into creating work that will be remembered as foundational for the genre as a whole. It has been incredible to see these artists put in effort to envision universes for themselves and their fans, creating records that act as referential material, even. I do not think integrating the radical notion that women are humans, not objects will disadvantage them in any shape or form. Instagram activism, in the absence of self-reflective change, does only so much.