Music and dance as arts have long ceased to constitute a binary. If singing ambles out of the chrysalis of the self, dancing—being an essentially visual art—amasses perceptions to create new selves with every footfall, clementful yet clamorous. As inextricable twins that nurture each other, the two arts also betray their cleft; the glorious delta where the balance between them is the bridge between personal and performing arts.

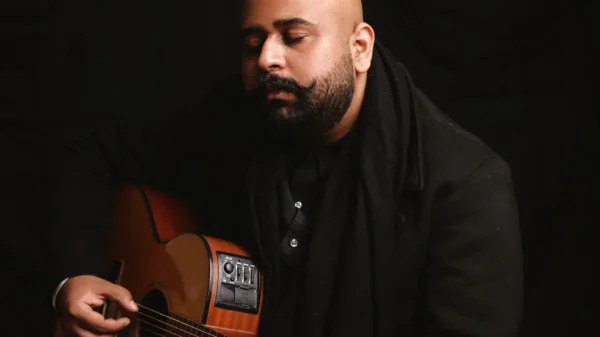

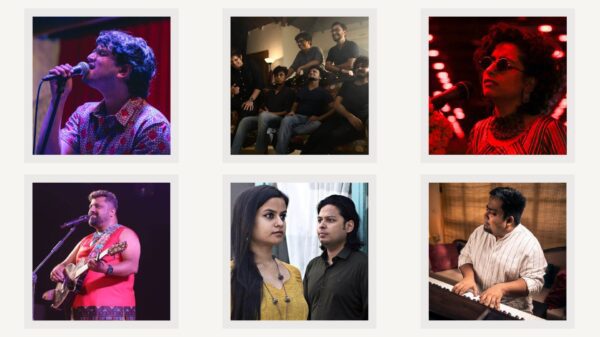

Dancing, interestingly, also is a masquerade; it is a game of flitting personas, of masques. So when Bangalore-based musician Jeevan Antony calls his latest outfit Backup Dancer, it certainly begs the question as to what he could possibly be alluding to with the moniker. As always, the answer is already there, in the music; getting to it however charts a journey that spins out from this land and goes far beyond it, shaping Antony’s sound alongside.

The Antony brothers—Jeevan and Mathew—have also been fond collaborators since when and where it all began, and their departure to Fort Worth marks the beginning of their sonic contrail. With his brother joining him on bass and Houston—whom he met at a party in Fort Worth—on drums and vocals, Jeevan Antony began what would culminate into the boyband Fou. Their debut and only album, Boy, is an eclectic treat, housing elements ranging from Indie Rock and Indie Pop to Shoegaze. A track like “Station Wagon” is full of a young melancholy in unrest, which travels to unabashed longing in “Don’t You Know”, finally finding itself in its fullest embrace with the joyous confidence of “December”.

The story of Madràs, named after where Jeevan and Mathew were born (the city was coincidentally renamed to Chennai in 1996, the year the Antonys moved to the Middle East) follows the same strain. Seeing Ben Hance perform live who in Antony’s words “… felt like he was visiting from another planet” was pivotal, with the former being enthused to join the party having been piqued by the set of Jeevan and his band’s. The sound of Madràs is more mature both in terms of sound and lyrics, with Antony “writing less impulsive songs” the whole time while playing shows in Fort Worth as Fou. The demos recorded while he “… was playing with voice recordings, memories, experimenting with production, [and] thinking beyond a 3 piece live setup” find their final voice in what is one of this writer’s favourite albums to date: Things Can Change (also known as thingscanchange).

Things Can Change is an album, both in the musical and the photographic sense. The ethos of Madràs bleeds into their debut album with the gentlest of ease, as diaspora come alive by the keenest of perceptions in Antony. It is an exercise in memory narration; tellingly, the first track, “Bangalore”, is pure sound: an amalgamation of the Indian city’s sounds and a young girl’s whisper on a gentle guitar backdrop. As the listener progresses onwards, what unfolds is a coming-of-age story that speaks as much of Jeevan Antony’s story as it reassures of its parallelism with the story of his brother and bandmate, Mathew Antony. “I said, brother lets (sic) leave this town”, croons (Jeevan) Antony in “Tasmania”, to “walk our way, until we’ve found a better place”. The move to this “better place” was also a two-edged sword: as Antony confides in a correspondence with the writer, even though the brothers’ identities were in a way soldered into Madras (the city), their following returns to “home” were always “… as visitors, and not residents.” What is almost self-evident is that Madràs’ sound is an unmistakably unique one. The single “To Have Found” (also known as “to have found”), released just last year (the first release, after a decade, since Things Can Change) too, is made of a familiar family recipe, with Antony alluding to his mother who “… says jeev (sic), cut your hair son and shave that beard of yours so / you can look like my sun (sic)” (“sun” refers to Mathew, nicknamed Sunny). The track too, like the songs in Things Can Change, is storytelling fodder; it is nimble, lithe, in a way that only a Madràs track can be. In 2019 came out the EP Thirteen, a three track puddle of rain coloured by Antony in its fullness. All three songs stay within the standard three minute mark; in their controlled brevity they are tonally expansive, with simple instrumentals and overlapping atmospheric sounds that reaffirm Madràs’ aesthetic commitment to a life lived with deliberate slowness. The confluence of instrumental minimalism and atmospheric loans does not limit itself to Thirteen; Antony, as we shall see shortly, expands it further the same year into solo projects beyond Madràs.

Jeevan Antony’s musical niche under his own name—the masque least heard of—provides a sound that betrays the fact that Madràs’ sound is his brainchild; it is a sound that has for a decade and more been his home. Even commissioned albums like Sounds of Himêya, Vol. 1 and Sounds of Himêya, Vol. 2, released with tangible proximity to Thirteen, get the treatment of his unique process of contemplative quietude: written and developed over the course of several dawns, the predominantly instrumental tracks are meditative and invite self-reflection on the listener’s part. On the other hand, Antony is nothing if not a lover. His Bandcamp exclusive “the same thing” is a prime example of Antony’s stress on the lyricism; words become sounds become words as alliteration takes over with Antony’s whispered lullaby to “drink dont (sic) drown / in dog eared sentiment”. The grainy demo sound only makes the song’s raw honesty more pronounced. When it comes to his latest single on streaming, “I Think im In Love But I Wont Let Me” (also known as “ithinkiminlovebutiwontletme”), it is a song that acts as a segue of sorts into Backup Dancer. A funky indie pop song, it is a delicate balance—or even as the title suggests, a deliberate restraint—between nonchalant romance and experiential introversion. With Backup Dancer though, the latter seems to fade away; the erstwhile lamenting lunarchild, now decked in sequins, gets to trot a stage that has since now always eluded him.

Fittingly, in the sunny Summer of this year, more than a decade after Madràs and Fou, Jeevan Antony released his first single as Backup Dancer. In an informal conversation just the month before, I had found the Jeevan behind the Antony, all candour, opening up about the act. The past decade had had its own share of ups and downs; the precedent of a utopian music scene in Fort Worth, disappointments at a desk job, and the solipsistic arena of Indian Indie that he found suffocating on his move back to India (barring a beloved project with Shreyas Dipali—Sleeper Class—that never got to releasing music), constituted a fervent need to step beyond this humdrum. As Antony notes, the shimmerings of Backup Dancer had always been within him, with their glitters caged by the eclipses of a life in limbo. He “… wanted to have some fun, explore… to write songs that made me feel the way I did back in college….”

The move to Bangalore was perhaps just the tabula rasa he needed as an artist to march out in a self-sufficient fanfare that was not bogged down with the expectations the other masks had hitherto raised and fulfilled. The debut single, “Week, and Its End” (also known as “week, and its end”), spanning just over the three minute mark, is an unabashed statement; a compressed manifesto of what Backup Dancer is all about. Coupled with the catchy and fast-paced instrumentals that form the credo of Indie Pop, Antony’s vocals and lyrics arrive as confident and debonair, with a glint previously unseen.

The cover art shot by Rema Chaudhary (who also shot the cover art for the next single) is tellingly complementary: bedecked like Bacchus, away from the constraints of memory, Backup Dancer dances in the absolute present. He is an absolute flirt in the song, approaching a woman as “This heart’s had a break-in”, for which she is “the prime suspect”. The familiar wordplay is present here as well (“-Miss… Are you taken” is a play on him wishing he is not “mistaken”) with her being urged to take “one two many drinks” for what is a weekend at the beach to remember, at the cost of forgetting the pathos of the mainland.

The second single, “The Wild and Unknown” (also known as “the wild and unknown”) betrays more of the man behind the mask: Antony opens the song with regret at being a “wallflower”, but since there is “no escaping” his beloved, he must sing his song. Playful, open to “kick a ball”, he still maintains the virtue of tepidity in love; in no uncertain terms, the refrain rings loud: “Lovers please slow down—you’ll ruin it”.

As the second single ushers into a clamorous end, Antony is still of two minds; as the effervescent youth in his body yearns to parade the proscenium, the experienced adult is still tremulous in burgeoning longing.

Backup Dancer, as the mild tension in the name suggests, is home to precisely the contradiction that shrouds Antony at present. Like Basho’s tryst with Kyoto, Backup Dancer in his need to savour the moment is already ahead of it; in dancing, he moves beyond the backdrop and immediately shudders back, making music in the pendulumic tract he charts at his wake. The music of course, reflects this contradiction; to the deliberateness of “Week, and Its End” lies the uncertain response of “The Wild and Unknown”. Even in the latter, in response to the apparent pastel of instrumental Pop, Antony’s vocals screech in a lo-fi production that is anything but unintentional. The mask then, at first glance, might seem unfinished and cocooned; deeper beneath however, the dancer is content in contradiction. As dance and music are far from polar, Antony has learnt that to be seen and to be felt are not mutually exclusive either. With juxtaposed emotions of hiding and seeking, Backup Dancer is a project with a lot of promise. As the listener dances to these songs they listen, too, for wallflowers do not cease to soothe in joy. As the petals turn to the sun and dance, they caress the stem that has seen better days and worse, hoping to bloom in entirety—a thistle with thorns—in the days to come.