If there is one place in India that has art woven into its fabric, it is Bengal. Historically, home to tremendous political and cultural capital, it is the only region that went through a significant art and cultural movement that went on to become India’s brand of ‘Renaissance’. The Bengal Renaissance was crucial in questioning ritualistic practices such as the caste system and Sati through arts, literature, music, philosophy, religion, science, and other fields of intellectual inquiry. From Rabindranath Tagore to Satyendra Nath Bose, the movement saw the emergence of important figures, whose contributions still influence cultural and intellectual works today.

Somewhere between The Bengal Renaissance and liberalisation, Bengal fell from grace as it ‘failed’ to live up to the rigours of capitalism. But the cultural roots run deep. While it is very underground right now, Bengal is showing the first signs of starting another awakening. From art to food to fashion, the younger generation is raising its voice in new and creative ways to bring the glory back.

The most envelope-pushing of these is the rich sonic diversity of the region. Always a hotbed for left-field music, some of the most radical musicians in electronic music have hailed from Bengal. For a long time, these musicians were lost at sea as a consequence of what was perceived as a stifling culture in the face of quick liberalisation and development in the rest of the nation. As the smokescreen begins to dissipate, artists are beginning to take the mantel anew and create a mark with well-produced, boundary-pushing experimental music.

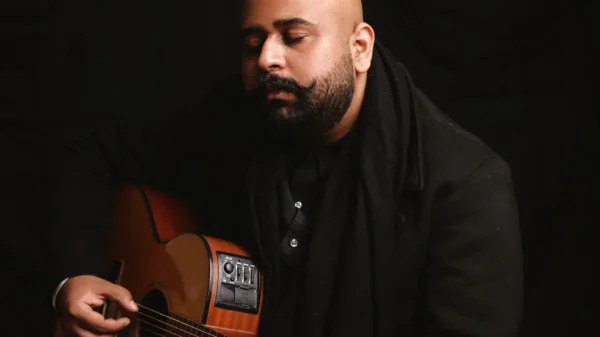

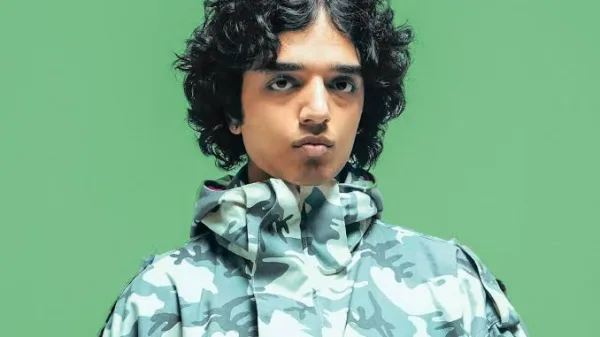

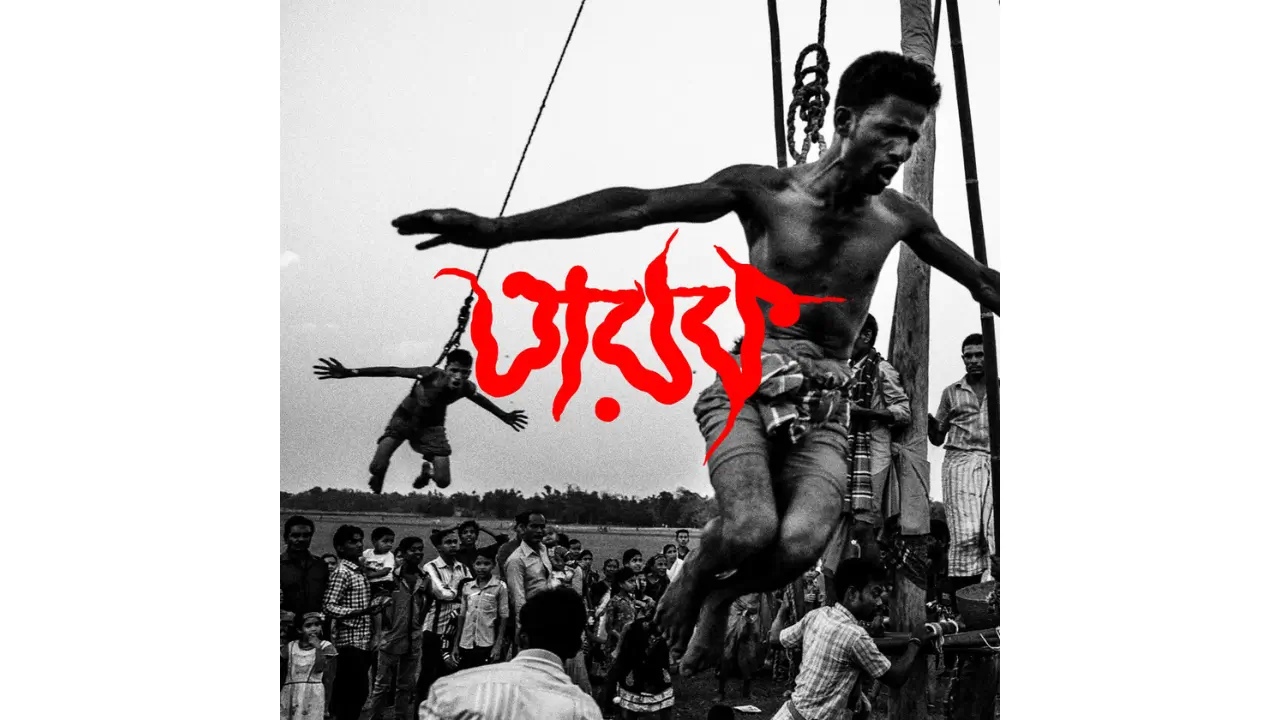

Among these is a movement that goes by the name of Biswa Bangla Noise. Named after the MSME Enterprise, Biswa Bangla, that the Government of West Bengal has set up to promote handicrafts and handmade products from the region, “adding noise to it is basically like a cheeky inside joke about putting Bengali Noise out there.” On the origins of how the label came about, multimedia artist, illustrator and musician Revant Dasgupta, who also manages Biswa Bangla Noise says, “We were mainly inspired by a lot of the Bandcamp Labels putting out Harsh Noise and heavy music, most of which were based abroad. So (we) thought it would be nice to have a Noise Label with a heavy Theme of West Bengal only featuring artists from the state or people associated with the culture. Though we have been looking to expand recently and have been talking about bringing in people from places like Bangladesh that share similar cultural histories with us. Kind of expanding on the term “Biswa Bangla” which translates to Global Bengal.” It is ironic that they were inspired by Bandcamp Labels because their latest release, তারক by Bengal Chemicals, was featured on the May 2023 list of Best Folk Music by Bandcamp Daily.

Bengal Chemicals has been a rising star in the experimental electronic music scene in Kolkata. As an artist, Pritam Das, the man behind Bengal Chemicals, is keen on making and releasing music, without thinking too much about what it means for his ‘sound’. About his inspiration for তারক and how it translated over time, he says “Nobody is going to make the kind of music I want to hear so I have to make it myself.

I have been doing a more elementary form of this since I got my first computer. Installed Audacity and FL Studio and played around without having any idea how it works, with no intention of making music or having any audience.

I came across Behala Boys Sex Club in 2020 on Biswa Bangla Noise, which was a big trigger. The next year, I came in contact with Revant Dasgupta and Rana Ghose. I think I sent some demos to Revant and then he sent it to Rana (or I sent it to Rana) and then Rana asked me if I wanted to play live. I was not sure what that meant but I was down. Most of the music I have released till now was made in January-February 2023. Doing it is pretty uncomfortable, I do not want to do this but nothing else makes sense.”

Many ponder on the intention behind listening to the noise, if any. Noise music is defined by the ability of artists to activate the noise to tell a story. Often though, it gets sidetracked by its inability to be anything except the harsh sounds. In তারক, Pritam artfully produces noise music that when listened to actively can evoke a sense of emotion in the listener – emotions that are able to detach from the creator and adapt to the listener. Pritam shares, “তারক after losing its pure meaning translated to English as a star/protector. The fact that stars are in a constant state of motion while at the same time seeming static in our perspective, a progression without any climax, the always arriving quality, represents the vibe of the album. Revant made the album art which I feel captures that effect so we decided to go with this one.”

Pritam’s straightforward but on-point description of its vibe is an example of how music can evoke feelings without being complex. The paradox of language is such that it is both a barrier and a connector. In music, this paradox is transcended to form connections with cultures whose language we might not understand but can appreciate with their sonic interpretations. তারক is very much an album of Bengal. You can sense it in the nature of the field recordings and sounds Pritam uses. Yet, rather than ostracising those who wouldn’t understand the language, it provides a glimpse into the culture from the lens of noise music. This could be attributed to the fact that like all folk music, the content of the album is not ‘about Bengal’ but it is inspired by it. In the end, the feelings are shared by the artist and the listener, the language could be many. About the field recordings used for the album, Pritam says, “It is quite sample-heavy to the point that I am only using samples in some of the tracks. I think I use samples as instruments. As early as I can remember, popular industry music from the ‘90s and early 2000s made me anxious and panicky. I am not sure if it was because my memory of this music was intrinsically connected to my rough childhood or something else. Using these samples allowed me to explore, process and accept memories on my own terms. All the samples featured on তারক were recorded on a Samsung M01 in and around Leningarh, where I live. Samples consist of but are not limited to field recordings of the mela, local functions, speeches and advertisements, baazar, traffic jams, industrial machines, railway vendors and Bangla pop singers.

Everything is a sample, Every sample is a track.”

That something as niche as a Bengali Experimental Noise Label even exists is commentary enough on the multidimensional nature of the region’s culture. Revant recognises the tendency of “music subcultures in Bengal to be mainly notorious for functioning within its own community and ecosystem, removed from the rest of the country.” With Biswa Bangla Noise and the larger experimental music movement in Bengal, he thinks it would be “interesting to see that change and to bring people together in a way.”

To be able to fuel a movement and curate a label, Revant needs artists who would be producing music that could make for a good addition to the label’s discography while also growing the movement. He says, “I usually am on the lookout for things that sound interesting on social media, Bandcamp, word of mouth etc, to talk to artists with an interesting sound, or people who don’t have experience releasing music but have an interest in exploring alternative music. And ask them if they would like to release something with us. We originally started off working with Harsh Noise and Power Electronics but now are open to anything as long as it presents an alternative approach and an interesting outlook.

For me personally, Biswa Bangla Noise is a space where we try to encourage people to come in and have a go at putting out music without stressing too much about things like musical proficiency or experience, or even what gear is available to them. The idea is to provide an open space for people to release music without judgement. Any curatorial focus is purely on expression, and based on what the artist wants to say, as opposed to how they say it.”

Many labels, over time and in countries, have tried to curate based on expression but have eventually been thwarted by the lack of resources. Currently, Biswa Bangla Noise is going strong on curating based on its ideology and paving pathways for the artists they curate. Bengal Chemicals has released two albums in quick succession on the label. Harsh samples recorded by Pritam dominate তারক. These are set against melodic drones and heavily distorted drum beats, all evoking a sense of chaos in the listener. As far as setups go, Pritam’s basic setup of “FL Studio 21, VCV Rack, Reason 11, FL Studio 10, LMMS, Audacity on a 2012 Macbook Pro” without any emphasis on the ‘gear’ is an ode to the power of an artistic vision meeting today’s technological advancement.

Pritam’s vision has allowed him to focus on producing work through the struggles that come with being an artist. When he is not making music, he is researching Nineteenth Century Bengal. Through his PhD titled, “Decolonising the Body: Physical Cultures of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Bengal”, he attempts to trace the significance of physical culture in shaping ideas of nationalism among the youth scene at the time. The nature of this study can be understood, if positioned within the larger framework of intellectual history/body studies, and contrary to, a study on sports history of modern Bengal. On the music front, after releasing the two albums on Biswa Bangla Noise, he has finished recording his third album “পবিত্র বিজ্ঞান” (Holy Science) which is set to release soon. Currently, he is obsessed with some Latin Tek/Cumbia artists. Reflecting on releasing music quickly, which is counter-intuitive to today’s practice of release-market-tour, he says “Right now, I am making quite a lot of music and I want to release it as soon as I am done producing a set of tracks that I feel can be collectively released. It makes sense to release it and move on to new projects. However, there are no intentions behind releasing in quick succession. Maybe after the third release, I’ll do something else or release more music, I am not sure. I don’t want to develop a pattern.”

Perhaps, we all have something to learn from Pritam, and Revant & their relentless dedication to creating the art rather than giving into the prerequisites of having an audience and marketing the work. In the end, we’ll leave you with the advice Pritam has for emerging producers,

“That thing you think is wrong with you is your style.“