Three years ago, when I had moved to Delhi from suburban West Bengal, the shift had felt monumental. An 18 year old who had walked through familiar dingy alleyways and past waste-covered playgrounds had just started living in a glistening metropolis, furthermore the capital city, the change was meant to be jarring. For a while, it had all seemed vacuous. Going to the glitzy spots in Hauz Khas, accompanying friends to posh art galleries, chewing on dismal amounts of food in Chanakyapuri cafes once in three weeks — all of that seemed nice enough ways to spend time, but it lacked the bite of suburbia that I had grown up with. Where I had been staying, the gentrified North Campus, also seemed like it lacked something — my parents, who had exhausted all their financial resources trying to ensure that I stayed comfortably (much to their own discomfort), could sense my cognitive dissonance with the city. I was almost sure that I would never absorb Delhi into me.

Things, however, were supposed to change extremely quickly. I had been into desi hip hop for quite some time, but my knowledge of the culture and the musicality was only surface level at best (it still is, but I would like to believe that it is mildly subterranean at present). A friend, whose commentary on music I have come to greatly value over time, had been quite passionately posting about one specific album, which eventually ended up immersing me into DHH as a genre, and opened up Delhi in ways I could not have apprehended.

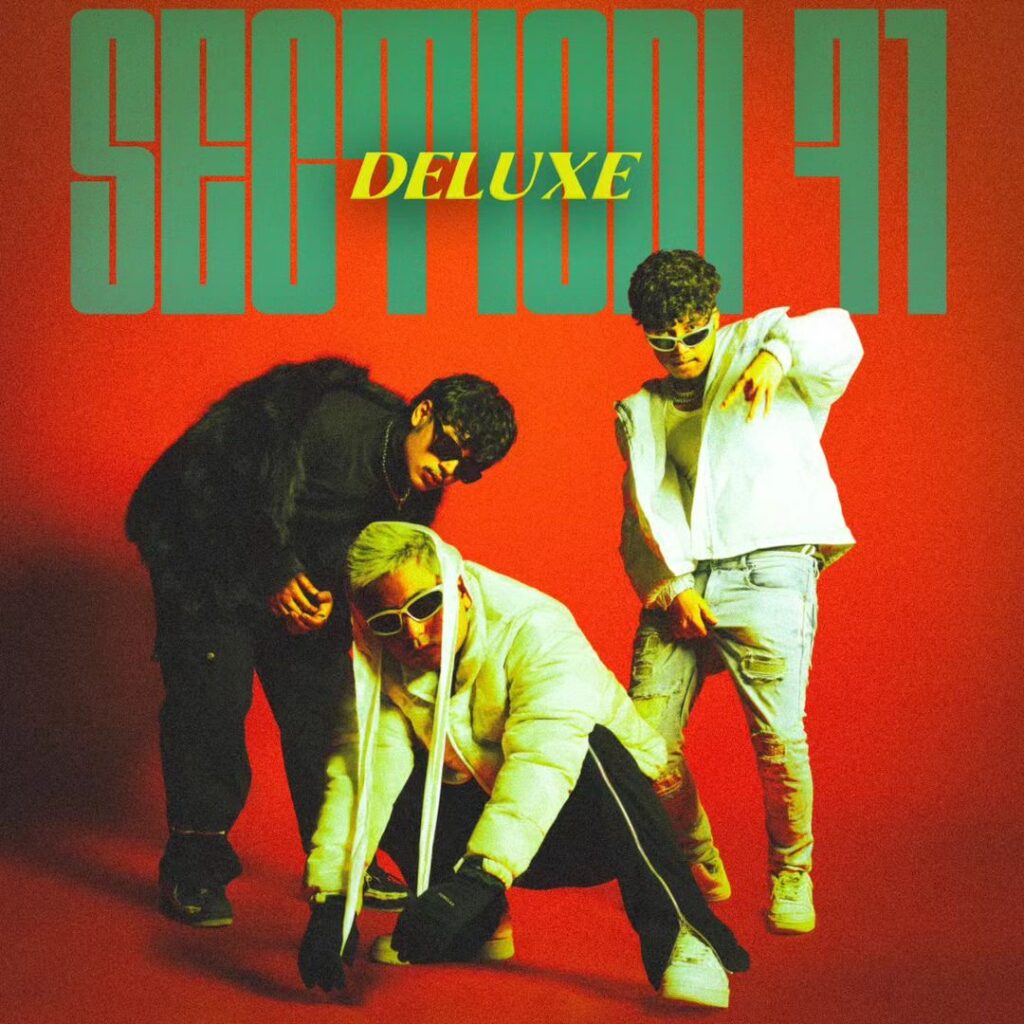

In 2023, three hiphop artists : OG Lucifer, Bhaskar and Lil Bhavi collaboratively released an album entitled Section 71 – with tracks that reflect clear musical influence of the latest generation of American rappers (the autotuned cadences of Travis Scott and Playboi Carti floating like omnipresent gods of direction when it comes to the musicality of these numbers) and the ever so continuous themes of the deprivation and the struggles of being from the “hood” that characterize almost every hip-hop single. However, there was something extremely distinct about the collective’s creative output that has garnered for itself a dedicated following which enabled them to carve their niche in a genre that has a burgeoning sense of self-determination, still overshadowed by the presence of a few solitary names that have gained Bollywood’s stamp of approval designating them as hitmakers.

In January 2024, the three dropped a deluxe version of the album – with features from almost the entirety of the Delhi desi hip hop scene (Seedhe Maut, Qaab, DRV, Frappe Ash and Pho being some of them). The album also offers gritty visuals of the parts of Delhi that do not feature in the ever so frequent Instagram reels of the city’s aesthetics. The 20 song album, although continuing with similar themes in terms of content, and sticking to an overarching consistency in the style of production — does not retain any of the songs from the initial album. Opening with with the eponymous Section 71 (which is a reference to the referred section under the IPC and the artists’ area code in Delhi), with lyrics that croon mentions of a singular corpse on the Dwarka Highway that the rapper does not bother turning back to see, feelings of ever-so-noxious disappointment looming in the Delhi air, and colloquialisms particularly characteristic to the khachras of Delhi (West Delhi, to be more specific, they already set the listener on track, readying them for what they should be expecting.

One of the standout tracks, for certain, is Tatta Giri, which also happens to be the first track that I had heard of off this album. Featuring Rebel 7, the track has the rappers altering their flows with their respective cadences and switching between satirizing and intimating contemporaries who they perceive as wannabes. The album is an interesting application of new school rap elements on extremely Delhi-typical vocabulary based lyricism — manifesting in tracks like Habit which start off with the rappers murmuring slatt, droning in intentionally applied inflections that implicate intoxication, drawing on the content of the track itself. The pho feature, Ukno, functions as an interesting interlude — almost reminiscent of a surprising SZA appearance on current male hip-hop artists’ albums.

With the three attempting to redefine trap music on their album to very personal storylines of struggle, anger aimed at people atop the social chain while being proud of their respective locations, they experiment with soundscapes that are similar to ones that one might hear in F1lthy produced numbers, with components drawn from artists like Lil Durk, Young Thug, Kanye West — and even, to some extent, 50 cent. Some other standouts include Medicine, Scarface, Uchalta Fajoola and Certified Plug. Asambhav, featuring Seedhe Maut, is perhaps the most appropriate track to put an end to the album — the three have gone on to tour with them as supporting acts with the rap duo who have climbed onto luminary status right now.

The album’s grit is assuredly its strongest feature — offering a composite system of a sound that you can associate with the underbellies of Delhi and the rage that comes with being a part of the city that is not in any way with a reflection of the refinement of the “classier” parts — instead doubling down on the ironies of classicism. Some tracks do tend to get repetitive, owing to the artists’ “signature lyrical motifs” sounding a little too unvarying when they appear one after another, creating and recreating the same image in the minds of the listeners — thus making the tracklist slightly predictable at places. What does become impressively prominent is its sense of honesty, and its unfiltered ambition, that triumphs over its weaker crevices.

Almost half a year has passed since I first listened to the album. A lot has unfolded in my life since then — but perhaps, in an odd correlation of sorts, the city has opened up to me way more than it has done in the past. I have made friends who share similar frustrations with how Delhi swings violently between cutting us open and stitching us right back up — roughly and tenderly, all at once. I have also found myself in parts of the metropolis where I have felt the same gnawing nature, in more visceral forms, that I used to at home — having walked through shabbier, more decrepit parts that seem so different from the curated picture-perfect image I had of the Delhi I lived in just some time ago. More importantly, I have gone down the DHH rabbit hole, observed cyphers at the Hauz Khas Deer Park, albeit a little sheepishly, and attended shows in covertly awkward ways. Maybe, there rests the triumph of any album, when it inculcates in you the need to engage with the palpable archaeology of the genre in itself — not just dive in, but stay immersed.