I have in the past, personally and professionally, expressed in no uncertain terms my attention to the curious case of eponymity in music. To name an album after oneself or after the outfit the artist releases it through, is, beyond a statement, also a very definitively confessional invitation to blur the lines between the art and the artist—to access the labour through the product. Eponymity testifies against the writer (or artist), as Barthes would have it, being “never more than the instance writing”; it is, in my view, the single most powerful postmodern resistance against the poststructuralist politics of écriture. If musical eponymity then is, albeit its admitted commonality, a phenomenon so charged, then to have an artist release an eponymous album which would turn out be their only release, certainly drives—even if retroactively—one’s reception of the work further to exponential depths.

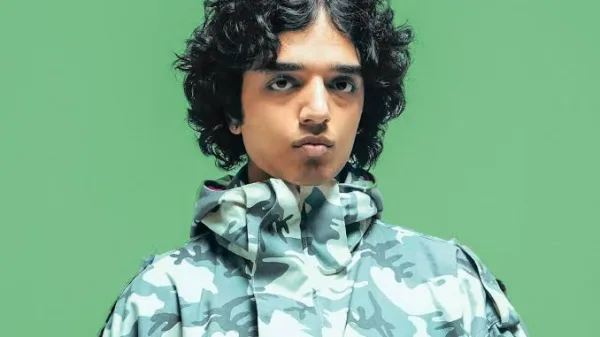

The early 2010-s in India were a period of fervent musical output insofar as independent music was concerned, especially in Delhi. The city, bustling with potential, was fraught with burgeoning talent, where screening and shaping it became a challenging luxury of itself. The advent of Pagal Haina as an artist-management house proved crucial at this juncture; shaping talents like Rounak Maiti, Shantanu Pandit, Dhruv Bhola and many more, Dhruv Singh and Lucy Peters—along with the rest of the team—proved to be of inimitable prescience, to whose effect their artist roster down the years leaves little to be added. Run it’s the Kid, a four-piece boy band spiritually and lyrically headed by Shantanu Pandit (primarily) and Dhruv Bhola, started appearing publicly and playing live as a band somewhere around 2013-2014. The latter was also the year when Pandit’s debut album, the infamously Dylan-esque Skunk in the Cellar came out, which provides us a neat context for his need for this band—this outfit—to try out tones, both in musical and thematic terms, that hadn’t found home in the rustic poetics of the five-song EP.

By the time Run it’s the Kid—recorded and mixed by Miti Adhikari of Kolkata—was born into the world in 2016, the band had lost its telling exclamation mark. It was initially called RUN! It’s the Kid, and it is in the capitalisation of the imperative verb and the not-so-subtle punctuation, that the core ethos of the outfit and its album lies. Apprehension, or rather displaced and projected apprehension, acts as a thematic motif of sorts throughout the album, and the obvious depressive theme that arises is only counteracted by a slim possibility that the love lost still has some to save. The solitary exclamation mark after the clamorous “RUN” is the apex of the apprehension that the “Kid” is met with, shunned because of his overwhelmingly clear difference and strangeness from the world (which is possibly innate, manifesting at times in exteriority), leading to his eventual—and often self-induced—ostracisation. (Primarily and overarchingly) Pandit’s kid is no dilettante in the love that has constructed much of his ideas of self—his ego, so to speak—to which perhaps little more stands witness than its resultant, inevitable, loss.

Run it’s the Kid’s almost decade-old performance at Speakeasy is a potent reminder that the goal of the outfit remained, like any outfit, at the end of the day, to enact a necessary masquerade. In the video, as a young Pandit takes the stage as the frontman with a gusto and slicked-back hair clearly taken from Elvis Presley’s playbook, the band seems jovial and free, even from the dregs of their own music. As their Bandcamp page attests, Run it’s the Kid describe themselves as a “moody waltz” project; by describing their music in terms of a dance form, it is almost as if the listener is presented with a learning manual—a push into what they believe the appropriate reaction should be to the music. Needless to say, Run it’s the Kid as an album is smoke on water. If the metaphor holds, the smoke of the music floats and dances around, sending the listener to keen physical lilts, all the while hiding the murky depths of the water of the lyrics that make it possible—the pain that makes possible the pirouette. The metaphor is presented at the outset itself, with the first song, “Forgetting How to Swim”; while nimble music sends the body in a sway, sinister lyrics—describing a relationship gone terribly awry—follow, marking the very first indication of the album’s self-aware duality. The broken lover has been called a “liar” and a “leech” in Pandit’s alliterative zest; like the necessary parallax error created by the disjunction between the music and the lyrics, it is clear that this relationship has been going on two different roads (or seaways), where the crooning lover felt in control with his hands on “the rudder” of the ship, while for the beloved it was already over: they were “under water”. The titular forgetting of swimming—an obvious metaphor for work in a relationship—then becomes an accusation disguised in diagnosis: before Pandit includes “You and I” (which is interestingly absent from the lyrics posted on Bandcamp) in the disregard, the song points first towards the impression that “… slowly you’re / Forgetting how to swim” (emphasis added). When “Love We’re Made of Porcelain” (which happens to be my partner’s favourite song from the album) rolls in next, the listener is already prepared to dig deeper into this relationship as brittle as porcelain. What they do not expect, however, is how high Pandit and Bhola’s songwriting is poised to take the listener, so the actual depth of the chasm becomes apparent in freefall. Likening himself and the beloved to “… soldiers / Born to take orders”, Pandit and Bhola establish a sort of kinship that did exist between the lovers; it was only that they were under the whim of forces that transpired beyond their control. Indeed, the lover was told that he was her “best friend”, and despite the aforementioned hand of fate, he is still sore, accusatory, and in denial of the implication that her “hands were [ever] clean”.

With a relationship so fraught with tumult and yet so deeply marred in longing, as portrayed in “One Time”, everyday feels like waking up “on the wrong side” of a bed that still beckons the lover every night. “The Big Parachute”, my personal favourite from the album, is perhaps the single best testament to the coexistence of pathos, poetics and euphonic phonetics in Run it’s the Kid. Rhyme pervades the verses, creating a music of its own that harmonises with the instrumental arrangement, while Pandit composes a sort of pure poetry insofar as the eclectic imagery of the song reads as elements of verses written with deliberate poetic intent. With the usage of a plethora of askance binaries—prose/poetry; trees/thorns; knives/plates; squeeze/hold—that on the first glance seem to embody the polarity of a standard binary before revealing that they are more alike than apart, the deliberate lyrical wordplay seems to hint at the ease with which the album hinges on paradox: the birthplace of pain and pathos, too, can erupt into song and stage, only if we are content to live with the parallax error. Life can still go on, even if it is a life in afterglow; as Dostoevsky writes, “… there’s a whole life in that, in knowing that the sun is there.”

With “A Great Big Scare”, the displaced point of view—viewing the self from a second person perspective—that results in the self-ostracisation of “The Kid” comes into full bloom. The excoriation is part self-hatred, and part social awareness; beyond the self-accusations of being “foolish” and “plain” now, he knows that his own gaze has been moulded by the other gaze that otherises. The lethal circumstance of pubescence—“the [facial] spots” and “… that dreaded / Head full of hair”—in a presumably middle-class household makes it more than anything, about “the clothes” that he wears, and it is the kind of situation where the awareness of the cruelty fails to not only make it less vicious, but also create any distance from the eventual susceptibility. “June” takes us back to the hope of coexistence; as an ardent lovesong, it still stands true to the fact that the lover, the beloved and their love once were “for real”, despite the fact that they stand at crossroads now, armed “With guns”. Unmistakably, it is despair and regret that reign supreme in “June” and the entire corpus of Run it’s the Kid, but here too, Pandit refuses “this painful song” of the present from existing without “… those kisses / From June” of the past.

“To the Moon” closes the album, with its opening suggesting that the traversal of the album echoes the traversal of the doomed relationship, too. As the listener navigates through the album spanning beyond the forty-minute mark, it is almost as if they walk the same ill-fated steps as the lovers, who fail to do right by each other despite enacting what they thought they were supposed to, despite acting like “soldiers” of love, taking “orders”. Love needs more than promises, desires and even arduousness. It needs replenishment, nourishment; in the words of the ever-timely Le Guin, “… it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.” The fact that Run it’s the Kid enjoys such seminal stature in Indian independent music owes, perhaps even more than to its meteoric nature in being the band’s only musical output, to its qualification as a concept album. In its unabashed commitment to the narration of a failed relationship stemming from incompatibility and at least one socially embittered youth, Run it’s the Kid succeeded, with little precedent, to make an album whose self-sufficient cohesion manages to not undermine, but underscore its tormented bereavement. It is a genie in a bottle, attempting to tear itself apart to a life outside it, with the bottle holding steadfastly. This precisely is Run it’s the Kid’s legacy, having had the clarity to execute a body of poetry so potently accessible that it stands the test of time with a surety that will perhaps never be beleaguered. Despite there having been official correspondence from Pagal Haina a while back hinting at new music from the band, there has been no further flicker of hope to suggest the materialising of such a prospect. While one should not hold their breath on that, it is always a good time to go back to the “moody” sing-song of Run it’s the Kid, if one likes their music like quicksand—if one is as prepared to realise that untangling love and loss is an exercise in futility as doomed as extricating sand from water.

In either case, one drowns.