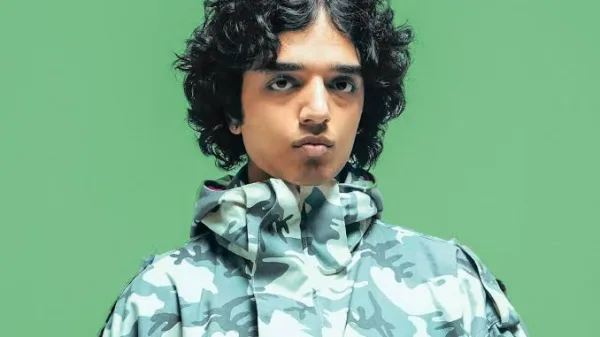

On an otherwise forgettable Saturday, when my doctor tells me that I have tinnitus, I stare at him and crack a smile at the comic timing of it all. A month before, I had finally decided that I wanted to write about music. Within a span of 30 days, a verdict had been laid upon me — one whose long term consequences I do not want to excruciate myself thinking about, although the irony of it all is not lost on me. To slap a bandaid over the new wound that had just opened up, I had turned to music, of course. If in a cruel twist of fate it all went quiet, I would want to remember what it means to listen to things that have the impact of filling all the spaces inside you with light.The Anirudh Varma Collective’s music had been recommended to me a few months ago by a friend who also happens to be one of Varma’s many students. While I had never anticipated that I would turn to contemporary Indian classical in times of incomprehensible, disorienting grief — somehow, over the last few months, I have found myself turning to it over and over again.

On the night I gain another reason to cry misfortune about, I turn to Perspectives — an easy, inadvertent choice, because the history of sound is always memorialized by its richness and intricacies, and this album exemplifies that right to the tiniest intricacy.The 2018 album has La Marée as its opener — is wonderful, ambient, and has a galactic quality to itself. Varma’s prowess on the keys is exemplified by the track — and has the clarity and aura of a number being played across a field, under a particular kind of sky, perhaps crowded by stars, perhaps blanketed in clouds — a quality of peace that I am unable to filter down with a typology of all things solemn. It transitions to one of the richest songs on the album — Colours of Jhinjhoti, a contemporary working of the Jhinjhoti raga, or more specifically 2 of its bandishes — and while it features some amazing vocal work from Jayashree Basu, Debashree Basu, Saptak Chatterjee, Kavya Singh & Ram Visakh, it is the instrumental arrangement that is a standout for this one. Abhishek Mittal’s guitar solo and Vinayak Pant’s sitar parallel each other in successive segments, and all of it is tied together by Aveleon Gilez Vaz on drums. The percussion and the flute form a sort of structural vertebrae for this particular number, and the entire album together, bending into the shape demanded while maintaining the dignity of a composite body.

Maru Bihag is beautiful — one of the many, many incredible projects that the late Pt. Sarathi Chatterjee has lent his voice to, this track has an impressive section of the maestro going head to head with another star in the ever stretching tapestry between heaven and earth. There is something very telling about Pt Sarathi’s voice — one can feel the airy lightness, almost laidback delivery of some of the most complex arrangements — a marker of the most seasoned grasp on Hindustani classical music, and it shows. One of my favorite segments on this one is a near-jugalbandi, where Pt Sarathi and Ahsan Ali’s sarangi go head to head with each other. The sarangi is poignant, like the rubbing of shaky knuckles, against the fibres of your heart, or maybe I am waxing poetic again — either way, Pt Sarathi’s voice and the instrument blend into and against each other, forming one of the best tracks of the album.Speaking of beautiful instrument work — one has to mention Champakali, one of the standouts on the album — especially with the sitar, tabla, sarangi and obviously, the drums. The percussion keeps this album cohesive, refusing to allow it to plunge into a sum of discordant parts.

Alhaiya Bilawal, performed by Gagan Goel and Shivash Shagti combines the collective prowess of the duo into a track that narrativizes, quite beautifully, two individuals in love craving intimacy. It combines an English verse into the reworking of the Alhaiya Bilawal raga. It is indubitably interesting — the juxtaposition of Jhanan jhanan bichwa baaje/ Kaise ke aau sej/Jaagat nanand jethaniya onto The night it calls out to you/When you touch my hand/when you walk my way/Your lips whispers our love song translates the artistic intent clearly. The album ends with Shankara — which the group contextualize as follows, “This is where it all began – A result of an impromptu session with Hindustani Classical Vocalist – Prateek Narsimha, back in 2013. The blend of two distinctive compositions creates a single, seamless harmony, in praise of Lord Shiv. The Raga itself is regal and formidable, and full of the shringaar and Veer Rasa. Anirudh always envisioned a big arrangement for this composition, prompting him to bring in a choir, an additional punch of vibrance. The percussive elements help to amplify the Carnatic flavours and context in the track. The track’s rich, full-bodied sound seemed to have been composed just for this album’s finale.” What I think I have realized I have come to adore about this track, and the album at large, is its strange sense of accessibility — and this is not meant to be a dig. I have 10 years of somewhat standard Hindustani classical musical knowledge behind me, but I know people who have found themselves completely immersed by this record and its construction.

What Varma and the Collective do is create a comprehensible complexity — not one that is banal, made to be forgotten into the recesses of time, built to float in and out of your consciousness without creating any impression of significance. Instead they play with elements, deconstructing it to bones, and reinvigorating with arrangements — almost like a surgical procedure driven by the rules of magic realism. Maybe, in continuation of that one unfortunate Saturday I have tried to dismember and dislocate in my memory completely, one day — the internal soundmaking will overpower the external. Until then, wonderful music like The Anirudh Varma Collective’s, and later, the memory of its depth.