If I were ever asked to use one word to describe my childhood, I would probably gravitate to “non descript”. Well, two words. It is not any cause for bafflement, obviously – there is usually not much to do in suburban West Bengal, there were even fewer things sprouting into the landscape of our otherwise dreary existences in the early 2000s (two decades within the framework of late stage capitalism is the equivalent of a lot more time when quantified by the amount of change). However, there was music, always. We had one humongous VCD player, a shelf stacked with cassettes and CDS, and one overly enthusiastic self proclaimed Bengali music connoisseur (my father) in our household. All these elements combined together to achieve their final form on Sundays, when I was subjected to everything that the man in question, with his undisputed control on the VCD player, deemed fit. A lot of this happened to be records of bands based in West Bengal and Bangladesh – the former of which were arguably in the last years of their mainstream glory.

While a lot of these bands were the source of a lot of pre-pubescent chagrin within me, one of them had managed to accumulate an uncanny amount of appreciation, considering more than half of the lyrics were beyond my infantile comprehension. Chandrabindoo, formed in 1997, and taking shape within the Kolkata college fest circuit from times before, had climbed atop my concise list of musicians back then. While I appreciated every song of theirs my father moodily blasted with speakers he got from Sealdah station, I was partial to, and continue to be, to their 2003 record : Juju.

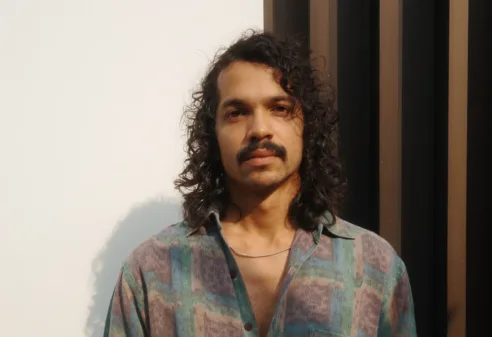

Juju, their sixth studio album, spans 40 minutes and 10 songs – and is the work of several artists, but three in particular : Upal Sengupta, Anindya Chatterjee, and Chandril Bhattacharya. I must familiarize the unacquainted with the band’s style of work. While many contemporary bands had built their fame off of their instrumentality and soundwork, Chandrabindoo’s primary USP was [and continues to be] its lyrics. Using humor, socio-political satire and embedding their album heavily in Bengali, and primarily relying on colloquial Kolkata, urbane, cultural codes and iconography – they had managed to build a steady fanbase transcending age groups. I need to, however, emphasize on the importance of humor, and its inextricable nature when it comes to the band’s essence — whose name is functionally a double entendre, one with the literal meaning being the last letter of the Bengali alphabet, and its idiomatic usage as an equivalent of an allusion to death, because of its finality of position within the lexical script.

This, however, does not mean that they do not play with soundscapes, elements and their influences on their albums. Juju, for example, features tracks with elongated vocal pitch-ups to hammer in the absurdity that they rely on, beatboxing, rap verses, saxophones — they take a lot from everywhere, blues, folk, rock — put it behind a Sukumar Ray – Anandabazar Patrika comic strip – derivative and departing encounters with Kabir Suman framework of lyrics, and create something so cleverly earnest that you find yourself enamored.

The first song on the album, and one of my favorite Bengali songs of all time, Mone, has Anindya in his oeuvre, as a hopeless, slightly pathetic-in-love guy singing about his “Mone” or the mind. The lyrics play casually with the idea of losing one’s mind and the other’s name in the wind. The trials and tribulations of the heart are many and incomprehensible to the mind, and the song tackles this bafflement with the sympathy of a friend that offers consolation from a place of concern and an attempt to make things less serious.

A personal favorite, and the one track that has recently taken over the Bengali reelosphere, is Geet Gobindo. This also happens to be Chandril’s solo, whose in-adherence to making himself sound like he is trying to hit the right note, or sing at all — comes in handy. His voice, that he intentionally hoarses up, and lowers, raises, and pitches down comes in handy for his distinct Kobiyal [Bengali folk poets, who essentially sing-song their recitation practice] cadence is perfect for the provocative, tongue-in-cheek lyrics. Starting out with “Tomaake dekhabo Niagara/ Tomaake shekhabo Viagra”, which translates roughly to “To you, I’ll show the Niagara/To you, I’ll teach [what is] Viagra” interspersing inaccurate Sanskrit verses to add a sense of misplaced gravitas to what is meant to be an unending display of devotion, it leads up to lines like “Shona boddo beshi jhawlmolao/Lift e otho ektolaaye/Beetles chhara onno poka khub boring” [Darling, you dazzle too much/You take the elevator to go a floor up/Every bug other than the Beetles is very boring”, and “Tumi amaar CPM/Tumi amaar ATM” [You are my CPM (Communist Party-Marxist, erstwhile West Bengal ruling party), You are my ATM).

There are more songs on the satirical-humorous vein, with the titular Juju, Aikom Baikom, and Awnko Ki Kathin, Maa Dake Khoka, Ki Aar Korbo– of which Aikom Baikom is the most eccentric, and a reference to a Bengali nursery rhyme making up its title. All of these riff off the members’ disposition of love and the conundrum of the city they inhabit. Something that appeals to me, in particular, 21 years after the album’s release is its distinct resolution to stay optimistic in all its resignation, heartache and frustration. The humor is not rooted in a sense of perpetual catastrophe– which is perhaps a blessing bestowed by its situation in time. The late capitalist sensibility of doomerist comedy, which I enjoy but do eventually seek a breather from time and again, had not set in completely yet.

One song from this album, that I go back to time and again, is Eita Tomaar Gaan (Trans. This Is Your Song), where the band takes a backseat from their constant slew of wisecracks thrown at you, and becomes earnest. Sung by Anindya, it carries some lyrics which have formed a point of referentiality in my brain when it comes to songs working with the profession of love – “Rawkto jholomol/ Ei khataar bhaaje gachher pataar naam/Eita tomaar gaan/Tumi nawrom thote sheccha byathar neel/Tumi onno mone aekla pakhir jhil” [Glistening blood / This notebook’s folds with the names of leaves of trees/This is your song/You are a self-inflicted aching blue on soft lips/You are a distracted lone bird’s lake.”

Writing this, I have realized how much time softens out isolation and points a flashlight towards whatever sticks out as untouched by all things of greater consequence deformed by some form of cruelty part of the human condition. I have realized how I have fallen into the cliched deathtrap of letting nostalgia even out the edge of childhood – but maybe that is what albums like this are for. To place a music-box in your handcream-bereft hands and go, everything was better than you think it was. This is your song.

Chandrabindoo’s 2024 album Talobasha, which they have released in vinyl form is available for purchase in vinyl form. There has been no digital release yet.