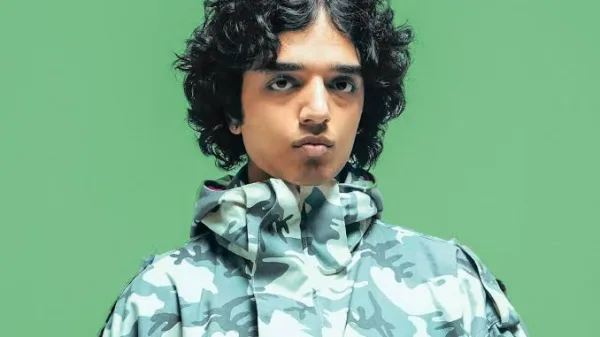

When I meet Dolinman, or more formally, Diptanshu Roy, in his 300 year old near-palatial home in Calcutta, in which he houses countless instruments, his love for vinyl [and a particular Moheener Ghoraguli original, if we are going into specifics], and the multiple spaces that he hosts his collaborative project, Dolinman X — it all makes sense to me. This is, in fact, the country’s first bluegrass mandolin player, the artist who self describes as someone who combines in his art, the folk traditions of Bengal and the Appalachia.

In their warm, well-lit, eccentrically artful living-room, I am greeted by Roy, and his wife and creative partner, artist and designer Karishma Siddique Roy. Together, they take me through the inception of Dolinman, the former’s trajectory in the Bengali music space as an instrumentalist and an independent musician, the independent music scene in the city, and everything that has culminated to the moment in time when I am seated across them, awkwardly in my chair, rejecting every offer of a beverage that is not a humble glass of water.

The Beginnings

Roy has been playing the mandolin since his childhood. “I was very shy, and I used to only play at home. The first time I played at my school was at its golden jubilee celebration, it was a huge hit. During my performance, the Birla family (LN Birla, SD Birla, etc.), were in attendance. They called my parents aside, and told them that I should keep playing, no matter what – and they would support me however they could while I was in school. The “support” in question was that whenever I played on the radio [All India Radio], or participated in inter-school fests, etc, I could take time off classes for rehearsals.” After school, Roy had given up on playing the mandolin, and picked up the guitar. When he started working in 1999, his music “went for a toss”. Roy, a self-taught designer, learned everything on the job – and was working 14-15 hours a day, even on weekends.

This period of departure from playing music had not remotely been the end. “The internet gave access to a huge amount of things which were unknown to me about mandolin. For instance, bluegrass. Bluegrass, as a genre, is already a niche American thing – so knowing about it in India pre-Internet was difficult. I had internet access ’99 onwards. I used to look up things about mandolin and bluegrass on Google, Ask Jeeves etc. While I worked my job, I saved up money and started buying CDs from America. Some of these reached, some got lost in transit. Eventually, in around 2005-2006, I got back to playing the instrument.” Bluegrass, Siddique, adds, changed Roy’s perception of what a mandolin sounds – miles beyond its erstwhile Italian associations in Bollywood.

“I had no clue that the mandolin could be played the way it is when it comes to bluegrass. That one could play chords on the instrument and sing, was beyond my imagination. On one office trip to Bombay, I went to Furtados and saw an Epiphone mandolin – at that point, I thought it was the best thing that I had ever seen. I bought it, and I started learning the instrument in this new light, listening to CDs and watching videos on YouTube. It was a journey, and then I co-created the first Bluegrass band in 2009 with Sujoy Chakraborty [2007, Siddique Roy corrects].”

Bands, Bengalis and Bong Grass

Siddique Roy tells me that in 2007, the band, NSA was formed. “Initially, the focus was to make jazz oriented music with bluegrass influences. Over the years it evolved, and later the proper band was formed.” They toured a lot with the band, and took it to several festivals/ places, including Delhi haunts like Balcony TV, Depot 48, The Piano Man etc.

“It was doing very well because we created this thing called Bong Grass,” the artist states. The band, No Strings Attached, or NSA were platforming this music, until some disheartening discord within themselves. Roy and his house happened to become a melting point for bluegrass music in India, and he continues to be visited by a number of artists internationally. Siddique interjects, “ There was a real conflict of ideology right there, and the NSA, unfortunately disbanded.”

The burial of the band however did not lead to the disappearance of the then-natal crossover genre that the artist had birthed. “The idea of Bong Grass occurred because I went to this Mandolin Symposium that takes place in California. I got a scholarship to go there, as I had applied there as a bluegrass enthusiast from India.” One of the players at this festival happened to be Mike Compton, a Grammy-winning mandolinist, who used to follow me because I posted my videos. He wrote to Roy, assuring that if he needed any help in coming to the US to play the mandolin, he would be ready to be of assistance. “I said that I wanted to come to the symposium, and asked him if he could write me a recommendation letter. He immediately did so, and sent me a bunch of Billl Monroe CDs that you would not find in India. Getting to the symposium, I was blown out of my mind. The best mandolin players were there, teaching, hanging out, and jamming with you. It was a huge exposure for me – to learn something here, on an island is one thing. To be in that zone, playing with the greatest, was another. One of my gurus, David Grismann, who was my mentor there, said something interesting – ‘In America, There are thousands of mandolin players who play the instrument better than you. However, if you play a bluegrass song in Bengali, then you would be the only person in the world doing it. That gave me the idea to combine the two things, it had already been at the back of my mind, but this gave me the vision to do something with it.”

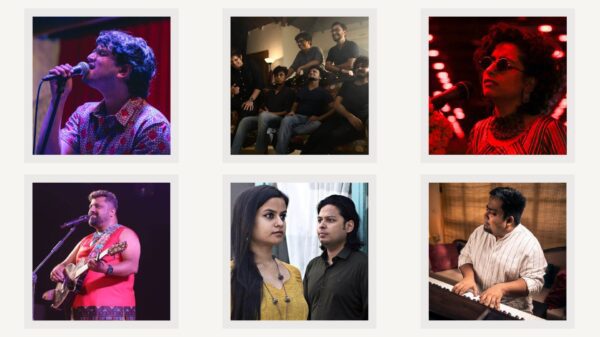

This was in 2014, after which Roy’s band happened and they started experimenting. They met Arunendu Das, who was also inspired by American folk music. He wrote Bengali songs on the guitar, and had been extremely enthusiastic to hear about Roy’s endeavors, and permitted the latter to rework a few of his songs into the bluegrass format and release them. Eventually, when Fiddler’s Green, his primary band which comprised him, Arko Mukhaerjee, Shamik Chatterjee, and Ritoban Ludo Das, came about, the artist incorporated a lot of bluegrass influences into their music. (Fiddler’s Green was formed in 2010, before the symposium. Bluegrass influences were already a part of it but Bong grass was formally named during the NSA years post 2016)

“It became a huge hit, and thankfully people know about the music, because we used to push that. We used to tell the audiences that we had put in bluegrass elements into our music. Things changed during the pandemic, because we were locked up in the house for so long. All the gigs disappeared. It was a difficult time for us. There were a lot of personal losses. I lost my dad, followed by her [Karishma] losing her mom. During the recovery process, the idea of Dolinman X came into fruition. The concept was to collaborate with artists from different genres, with the only constant being the mandolin. The fact that the mandolin could be the centre of the musical piece was not something that had had much prominence. A huge part of it was also documenting the house. You can just sit at home, and with good equipment, you can do anything. If I were to work in a studio, and mix and master everything, I would be able to put out only 5 songs a year – but I can put out 30 if I did everything at home,” Roy says, as I stare at the corner of the room that they have filmed a Dolinman X video in.

Of Creating in Collaboration – Dolinman X

Dolinman X is, based on what I glean from the duo, deeply entrenched in the idea of community building. The creative process, in itself, is very collaborative – with Siddique Roy recording the videos, and putting in her own vision towards the same. With the artist working with a bevy of young people, he regained a lot of his energy – which led to the project gaining popularity. The mandolinist also understood and got insight into what the younger crowd is listening to. The ethos was to invite an artist home on a Sunday, have food, leisurely conversation, and record whatever they played. He would then edit the video, and mix the audio and put it out.

“The idea of Dolinman X is that both of us subscribe to slow living, and Kolkata epitomizes that, says Siddique Roy, “We live in a society where everything has to be perfect, polished and filtered. I guess, because we are millennials, the analog generation – we respect the imperfections. We wanted to put out something real, homegrown, and indie, devoid of overproduction – and also a documentation of a musical conversation. The artists coming over would be people who know each other, or sometimes people who are meeting for the first – so something really beautiful unfolds in the space in between. Something really new opens up among us. That is what we try to document, we try to create a space where further conversations take place. It is experimental, and everyone is stepping out of their comfort zone.”

As Roy emphasizes to me, the music scene in the city is fragmented, and only the band hangs out with each other. The couple have attempted to end that sense of boundary. The previous year,9-10 artists came together under the project’s banner, and put out a Moheener Ghoraguli song, which ended in every creative involved coming closer to each other. This prioritization of this sense of uniting, putting things out collaboratively, brought the new record about.

Kurchi Phuler Desh

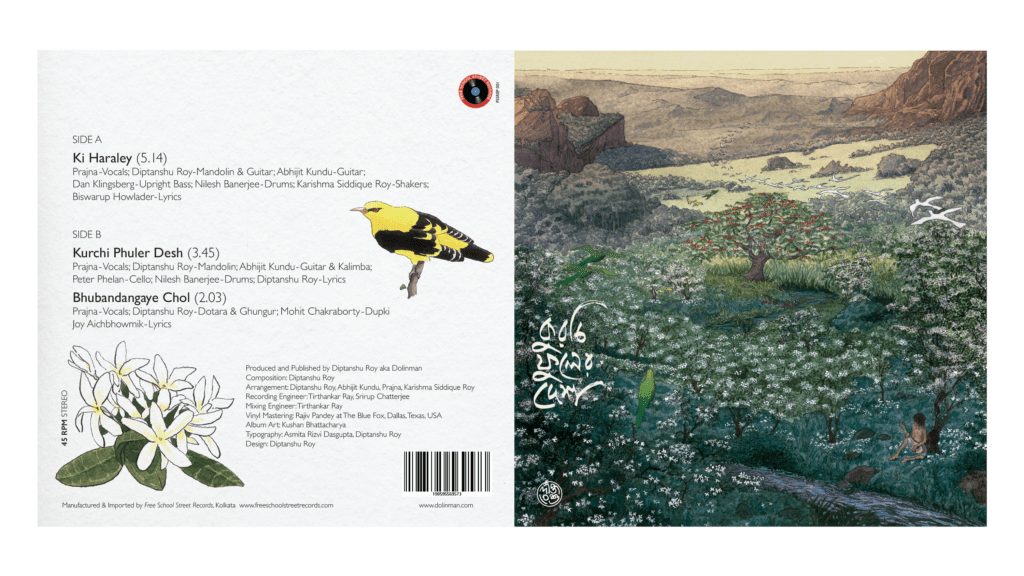

A long-standing demand that had risen from Dolinman’s audiences was the need for originals. Originals, as one knows, take time. While working with Abhijit Kundu and Prajna on these said tracks, they decided to put out an EP. Kurchi Phuler Desh features a plethora of artists, and has been born out of the efforts of Roy and his friends’ songwriting and arranging, coupled with the work of international collaborators – Peter Phelan, and Dan Klinsberg on cello and upright bass respectively.

One of the ways to put the music out, would obviously, be to put it out on Spotify. However, Roy decided to do something different with these originals – by tapping into the revival of vinyls. It is not, however, his fascination with the indestructible quality of the medium, at least not singularly. The artist, who has long been a huge fan of Moheener Ghoraguli, has one of the band’s first vinyls. Inherited from his father, the record came out the same year he was born – and happens to be one of his most treasured possessions, with him safeguarding it for this long. Taking a page out of the band’s book, and honoring the sentiment he has attached with the record, he decided to put out the EP just like his source of inspiration, emulating them by releasing the songs on a small vinyl. He had been eventually discouraged by Free School Street Records, who informed him that the cost of production of a small vinyl is almost the same as a large one. However, Roy had been persistent on the pessimistic arithmetic failure of this, and instead turned his head towards what he wanted to do, “The interesting thing about physical media, especially since nowadays we do not really connect with the music we listen to. We can skip, turn it off, etc.When you have a vinyl in your hand, you are buying into an experience, you are investing your time and money into it. It is yours, forever. You have to nurture it and take care of it. This is why I decided to give my audience a choice to participate in this experience.” This return to the vinyl has not gone unrewarded;, in almost over 40 years, Bengali music [in West Bengal] has been pressed into a vinyl record in EP form.

The record is titled Kurchi Phuler Desh in memory of Roy’s father, “My father was a big fan of gardening, and we have been frequent visitors of Shantiniketan. On our way to Shantiniketan, he once told me about the flower. It is a kind of jasmine, white in color, and has a wonderful fragrance. The tree becomes bare in winter, and in summer, before the return of the leaves, the flowers bloom. You can find the flowers on the Visva Bharati threshold in March-April. Baba once asked me to get a sapling so that we could plant it here, in our home. I had done so, but unfortunately it did not survive in the weather here. This was a long while back. I have brought one back now, and this one’s lived and flowered. In the midst of coming and being, the smell of the flowers became intoxicating to me. This one time, when we went to Visva Bharati, on our trip to Shantiniketan — I used to go on walks around there. There is a tree there, and I used to sit under it. The song is about being stuck in a room, and how nature calls you out. Most of my life has been spent in being trapped in a cage – and by that I mean within the walls of an office room. The true calling — the feeling of belonging in nature, the happiness that we feel in nature, we can never feel within the bounds of an office.”

Folkpick – An Archival Project

The artist also runs an independent label called Folkpick, Siddique reminds me, which is reflective of his interest in Bengali folk music. My interest in music from the north-east, northern West Bengal, and bauls, and documenting it to form an archive of sorts formed the thesis of the project. It is through this project that I met Sally Grossman, and she used to run a non-profit organization called Baul Archive, “She got in touch with me, saying that it was great work and that we should collaborate, and everytime she visited India, we used to meet her at her specific suite at the Grand Hotel.” Grossman passed away in 2021, prior to which she had last met the couple at a Christmas dinner pre-pandemic. Folkpick, unrelatedly of course, is also currently inactive, although its curations and productions are available to be accessed on YouTube.

“The reason I brought Folkpick up, is because I believe it all adds up, where Dolinman X began, where Fiddler’s Green found some of its roots, etc,” Siddique Roy has been documenting most of her partner’s creative projects, and she tells me that the pandemic put a lot of things into perspective for them, while I am treated to a wonderful lunch and an opportunity to listen to the prized 50 year old vinyl. Recording at their 3 century old house is also a tryst with time in itself, considering that its future continues to be uncertain – although the couple have tried to preserve it in all its history. “What we realized during the pandemic is that art can really help you, especially when everything shuts down. This whole idea that art is irrelevant, not lucrative, was disproved during the pandemic with people trying to heal by turning towards it. Secondly, the temporal nature of time and everything else weighed down on us. We were going through a lot of mental health issues, and these were the lessons that we learnt – through the medium of music, and we wanted to put that out. We are appreciating life in a whole new way, now.”

The Kurchi Phuler Desh vinyls are available for purchase on https://dolinman.com/home.