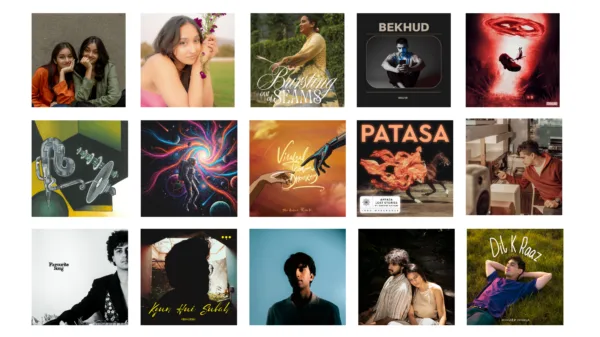

Ever so rarely, one has the opportunity to meet a person so full that their sense of completeness seeps into one’s own being. This is heavy praise, but absolutely true of my meeting Pune based Karshni Nair — mononymously, and more famously known by her first name, — who speaks with such startling clarity about herself and her work, that the artistic behemoth of a record that she has recently dropped starts making sense. The singer-songwriter-producer has been on a roll the past year, lending her voice to critically well-received collaborations with her peers within the alternative space (namely, shauharty’s Delicate Ache of the Unknown, Rounak Maiti’s Learnt my Lesson, and philtersoup’s I Know You’re Here With Me), performed across cities, putting up shows that cross over from being just performances to intimate experiences at an impressive degree of quality and vision, and helmed the creation of her debut album : BUCK WILD.

Going BUCK WILD

As she sits across me, armed with two phones in the aftermath of having broken her old reliable one and the consequent struggles of data transference and acclimatization with new technology, Karshni tells me that she heard the phrase, buck wild, in 2024 : “My friends used the phrase. I just thought that it’s such a great one. The shape your mouth makes when you say it. The way you project it. It’s so, like, hard, you know. I looked it up. I saw the phrase originates from the bucks’ story in the mating season — and I started reading about that stuff. You know, the way they behave : they go blind with lust.. That idea was intriguing to me. And in 2024, I also underwent a huge change in my body. And then this lust started building up — just going blind with it, just searching for the right one to, you know, fill some kind of void. And then, the bad experiences came. It’s just, like, a collective, a compounding effect of being in Bombay. The city being really loud. All these really personal, internal changes happening to you while also just fighting to remain yourself through that, to remain the same — through all these things that are happening to your body, actually.”

BUCK WILD, I realize is a tapestry : born out of harrowing experiences that Karshni has had in the recent past, ones that have driven her to write almost instantly, and reworkings of songs that she had previously put out and instinctively knew fit into this opus : “In September, I think, there was a show in Delhi that we played at OddBird. And something happened after that show that, like, really changed my… It made me really angry towards every man around me. I came back home and I just wrote GAPING HOLE and MALAPROPISM on the same day. And I recorded it. I was like, this is it, this is going to be the record, but why? Because these things are telling two different stories.

One is asking your name. And the other is pushing it away. So I felt that there are these two halves, and I needed to construct something between them. DINNER is a song that was put out on Bandcamp in 2022, which I’ve produced again for the album. GIRL was put out in 2021. Again, remastered. MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY was on Bandcamp. I just have taken some of the songs that I had and restructured them according to the kind of narrative that I have.

I was also reading — I read The Laugh of the Medusa (Helene Cixous), and that changed a lot of things for me — the whole idea of our bodies just being able to create infinitely. I guess I wanted to put my little things in a body of work.”

On Protruding Teeth and Sonic Architectures

MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY, placed sixth on the tracklist, had piqued my curiosity on my first listen – especially in its sardonic sense of humor placed bitterly into the lyrics, like a string of words meant to surprise you with its violence but also make you laugh, simultaneously [here is an excerpt : Cruel, talking to you rude / Duel? Oh, I would be a fool / Knock my protruding teeth out of my mouth/ A shutter goes off somewhere/ Behold the mighty ouch]. When I ask her about it, the artist almost bursts out laughing, “I have protruding teeth and I underwent a lot of dental treatment when I was a kid. When I was 11, they took a photo of me and they were studying it at AFMC — and my photo was in the orthodontics department. Anyway, at least they got something out of it, I’m glad. I’ve always been very conscious of my mouth and my jaw, and that’s why it’s called that. But mostly it’s like the gaze, I am conscious of who’s looking at me, and how sometimes when we try to do ourselves up for men and look good for them, maxillofacial surgery is about doing the opposite of that. Just punch me in the face instead of liking me. I’ll look how I want. Just, you’re so enraged by the way you’ve been acting, trying to lure someone in with something that exists universally. That you’re just tired and you just want to be punched in the face for your own stupidity in order to just escape that feeling of wanting to be liked. So that’s what it really is. But yeah, the knock my protruding teeth was like … I’m gonna name it maxillofacial surgery because this is too close to home.”

The writing on this album is incisively self-revelatory, as apparent in the way Karshni speaks of it. The singer-songwriter is almost dangerously unabashed and admirably brave about the clarity of her outlook of things that have happened. The fact of the matter has been clear to me since my first listen : here is an artist truly interested in herself, the totality of who she is. It is also apparent in the asymmetry that she chooses for her lyricism, which at a glance would perhaps look like poetry — perhaps an inheritance of what she sheepishly admits were her slam poet days. However, a lot of it is also about intention, she makes it clear – the incisive nature of her songwriting is not an accident, “These songs are written at different periods of time in my life. And so, I would deal with my vulnerability in a very different way. So, say for instance, Dinner, which was written in 2020, or Girl, are almost foolishly vulnerable, naive. Almost, in their healing or in their want for that person’s attention and touch. But, MALAPROPISM — there is a lot of distance between what I’m feeling and what I have written. I’m feeling it, but I have written very cut to cut, like, what happened. I’m not writing : I felt so hurt by you. I feel so sad. How could you do that with me? I didn’t put it like that for a reason. I think that that kind of distance makes it more effective when someone is listening to it, because they are allowed to imagine the feeling way more then. But in something like an interlude, I was just f*cking broken when I wrote that. There was no other way to write that, you know, apart from putting your heart out there. So, it also depends on what you’re writing about. If you’re writing about someone who’s made you mad, you want to detach from it a moment and see what exactly happened, almost like a reportage in different vignettes, but I don’t think there’s any consequence of that. I don’t see why I wouldn’t write something almost embarrassing. And maybe there’s some kind of pleasure in it also. That there’s some weird masochistic thing going on where I know I’m being perceived and it’s almost like : see, this exists and we can be like this also. And I want you to look at it, you know, I want you to look at the whole.”

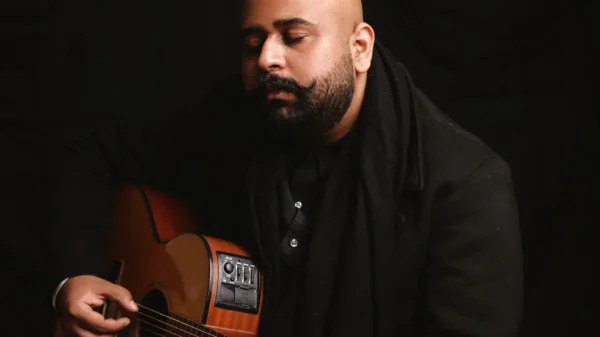

Karshni has been making music since 2018. In the beginning, it had been a duo job : recording covers with her best friend, in each other’s houses, and putting things up on Facebook or Instagram. However, she dates back her inception as a writer to when she was 18, after she had an exceptionally bad birthday, which eventually led to her putting the song out on Facebook, to positive reception. It has been a long journey, ever since, from switching to BandLab which had enabled her to discover the realms of layering, to using Ableton in the pandemic, with the help of a number of her producer-friends, who she credits with helping her get over the initial intimidation. In the roughly five-odd years that she has been producing music, Karshni’s sound has gone through a change, metamorphosing from her indie-darling sonic identity to much sharper, brutal and more experimental beds of sound. She attributes the shift in sound as both gradual and sudden. A lot of it has been due to the kind of work that she has been exposed to and participated in, be it philtersoup’s IDM projects, Fox in the Garden’s surf rock sensibilities, or Rounak Maiti’s recent turn towards shoegaze. “It was just a lot of very different things happening at once,” she says. Alongside, she began listening to Desi hip-hop more seriously — first through Shauharty, whom she also worked with, then RUAB (Dhanji), and eventually hip-hop more broadly. Freddie Gibbs, Westside Gunn — their vocal delivery and conviction, the latter of which she feels can be borrowed in folk songwriting : “They’re so free. They’re using their voice as an instrument in so many places. And I felt like that conviction is missing from folk songwriters’ work — not all of it, some people do it — but from what I’d heard. So I thought, why not combine the two.

In terms of production, I think I’ve always had this kind of weird sonic-art thing going on — scraping sounds, droney textures. That was always there. The moment I touched Ableton, that was there. But the changes in my delivery and my writing came from hip-hop. MALAPROPISM and GAPING HOLE especially — the delivery on those is very inspired by rap, by how people perform on a rap song, like they were born singing it. Like everything was building to this.

And also Imogen Heap — the way she sings, it’s strange and otherworldly. I wanted to really rinse the meaning of every word I was saying. That’s where the vocal performance comes from, really, across all the songs.”

Intent For Viewing

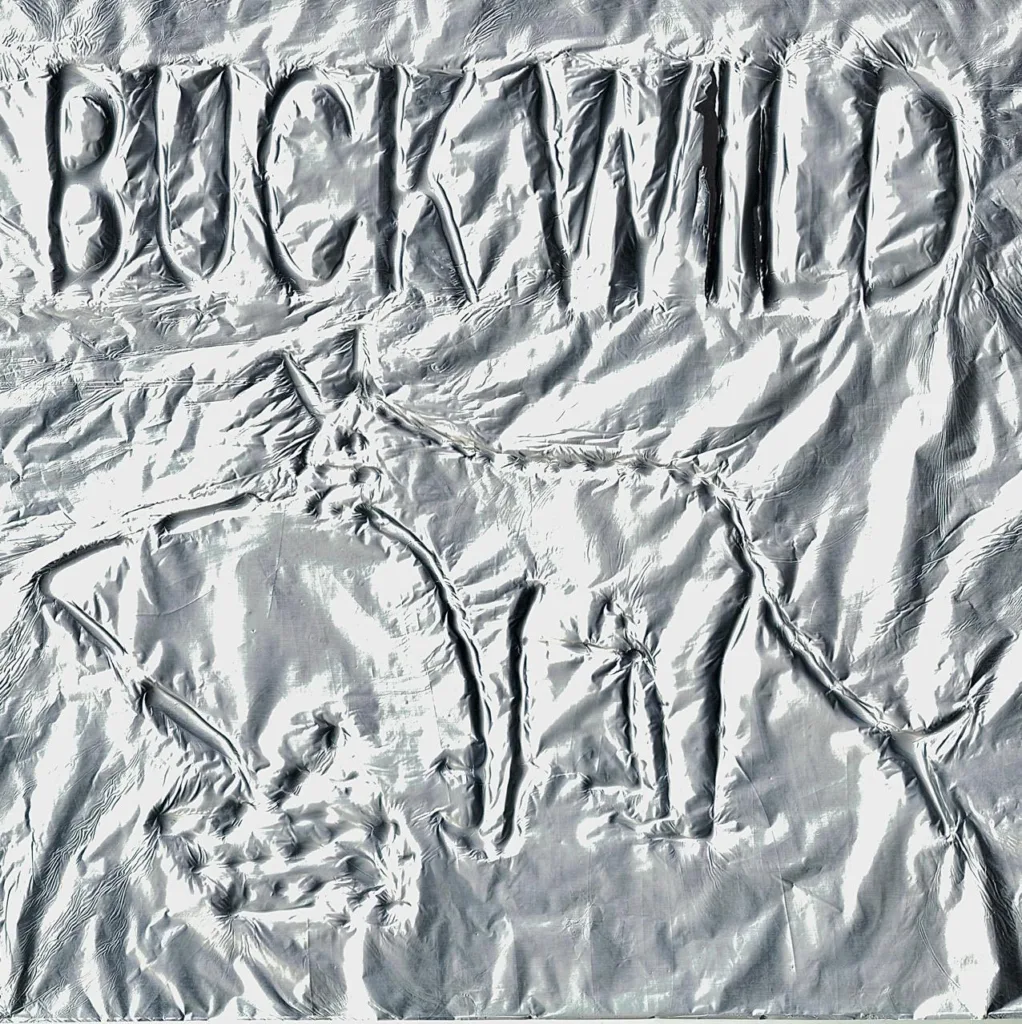

The aforementioned creative intentionality is not just limited to the album’s sound, but also the operatives of the kind of visual identity it creates and curates for itself. Karshni describes the album artwork beginning as a fairly instinctive drawing — a strange, almost creature-like form spitting at the edge of a canvas, with the spit hitting the boundary and falling back into a puddle beneath it. She had not been thinking about what it would be used for at the time. Months later, sometime in early 2025, she ended up placing the words Buck Wild above it and realised it already looked like album art. “I thought, okay, this is going to be the artwork. For some album.”

At some point, she took the piece to her friend and multimedia / visual artist Saba Mundlay, who had immediately connected with it and suggested working with something silvery — foil — referencing the inside of condom packets and separators. They had experimented with using a glue gun, letting it dry, and then pressing foil over it, creating a textured impression. One of the earliest tests was a foil rendering of The Body Remembers, which later appeared in one of the posters.

“There’s something off about it,” she says, “When you look at it, the tail of the creature, it’s not even a buck. It doesn’t have antlers. But there’s just something about that artwork that screams.”

The visual identity for BUCK WILD is interesting. Born out of dialectics with her gender identity (further exacerbated with her recent discovery that Gaping Hole is a genre of gay pornography and the metaphorical implication of her association of lust with the same), sensuality and the narrative of the album — the rollout, so far, has featured two music videos — for GAPING HOLE and MALAPROPISM. For the former, shot in collaboration with artist Priya Panchwadkar, the artist had found herself in Vetal Tekdi near Pune, running about in the forest in a white dress gifted by her friend with a couple of flashlights, in an attempt to convey the imagery of a deer caught in headlights.

The latter, a collaboration with shibari artist Amiya Bhanushali, has her bound in ropes as she stares at the camera confrontationally while singing the words : “I knew I wanted to make something with Amiya back in 2023, when I first saw their work. I really liked how calm it looked. I never thought I’d be into something like this — I was just thinking of asking them for a session. I was hesitant back then.

Then I made MALAPROPISM and thought, what’s better than being bound and singing these words? Because it clashes so hard with everything I’ve felt. There have been friends, people I know, who’ve made me feel certain things. And I felt like I could finally say everything I wanted to say while being bound — while being in such an intimate space with someone.

It’s a hard emotion to articulate. The song is like — you’re tied up, but you’re also thinking about all the times you couldn’t say what you actually wanted to say. So now I can do both. I can be tied up, and I can speak.”

BUCK WILD is out on all streaming platforms. Karshni is set to perform at MAGNETIC FIELDS NOMADS in February.