Hip-hop’s longevity and broad based appeal can at least be partially linked back to a key feature in almost all tracks within the genre – sampling. Of course, sampling has become instrumental in almost all forms of popular music today, but hip-hop almost constructs itself on the interpolation and reuse of other works. As Mark Ronson elaborates in this thoroughly insightful Ted talk, a single 1980s track called “La Di Da Di” has been sampled in so many popular songs, to create sounds so different from its own, yet altogether entirely reliant on its base composition. And samples need not limit themselves to just an element of a song being used in another. Everything from film audio to famous speeches have been used by rappers to add something distinctive to their work. Here in the subcontinent, the burgeoning hip-hop industry is beginning to take note, infusing sounds from our culture to pave their own path in the now global community that is hip-hop.

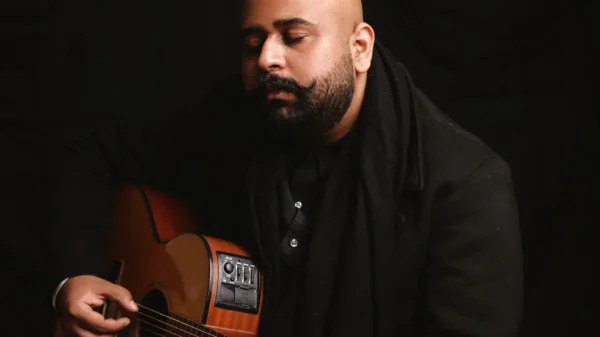

“PARIMAL SHAIS! HANUMANKIND!” As far as producer tags go, the Southern producer/rapper duo crafted one built to be instantly recognised. What makes their sound stand out so markedly amongst the increasingly over saturated hip-hop community is their affection for using instruments and samples that create a sense of “Indianness” in their music. Whether its the tabla beat that HanumanKind spits over on “Southside“or the violin interpolation used by Parimal on “Pharmaceutical“, they stand apart from Western hip-hop despite the English delivery. But the tracks that really grasped my attention, and particularly drove me to write this article, were part of an IGTV exclusive series that Parimal Shais has been coming out with called “Curry Chatti Beats“. By the producers own description, the series “is to have fun while grooving to the nostalgia of vintage aesthetics“. Using clips from old Indian movies, both visual and aural, the end result is a seamless blend of nostalgia with hard hitting hip-hop beats and bars. Rapping in native languages and using instruments authentically from the subcontinent are undoubtedly some of the ways for Indian artists to stand out. Sampling offers another avenue, it allows them to target cherished memories and almost reinvent their meaning to new audiences through creative mixing. In the first edition, a 70s Malayalam film called “Nazhikakkallu” is used to give the track an eerie and nostalgic backdrop before the bass claps in and HanumanKind goes off with “Now This That Southside/Do or Die/Who Am I”.

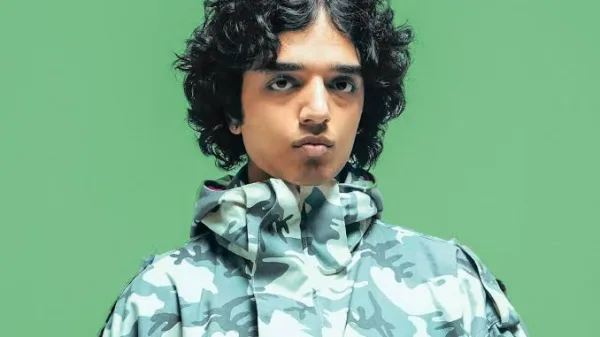

Producer Vedang‘s May release, Shastriya Hip-Hop, sees this concept of tradition mixing with modern reach its zenith with his array of samples from classical Hindustani music. Each of the five tracks take an original classical song, such as “Mi Radhika” in Vedang’s “Radhika”, and rework it around bass boosted trap drums as well as the occasional infusion of electronic sounds to further amplify the multi-genre feel. Five tracks long, but only nine minute in length, the short compilation does wonders in combining music that is so uniquely Indian with the most popular global genre of music. Not only does it succeed from a purely sonic look, but also for what it does for Indian hip-hop from a macro perspective. The more artists like these experiment and combine sounds intrinsic to our culture to hip-hop, the more powerful the end product becomes.

Hip-hop in India is still, for all intents and purposes, in its infancy. In both the independent scene as well as the mainstream one, old faces are beginning to become household names as new ones scramble to gain recognition of their own. In their quest to carve their own niche, nuanced usage of sampling will go a long way in pushing these burgeoning artist’s careers forward. Whether it be Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, or Jay-Z, pretty much every hip-hop great has liberally used samples from music, movies, and live recordings to add just that something extra to elevate their music. As more and more Indian hip-hop begins to be put out, songs that soon become established as classics could be memorialised by how future generations interpolate their sounds. However, for now, what needs to happen is a further exploration of existing and endemically Indian sounds to truly push Indian hip-hop towards becoming a genre that stands out as something to be heard in the global community.