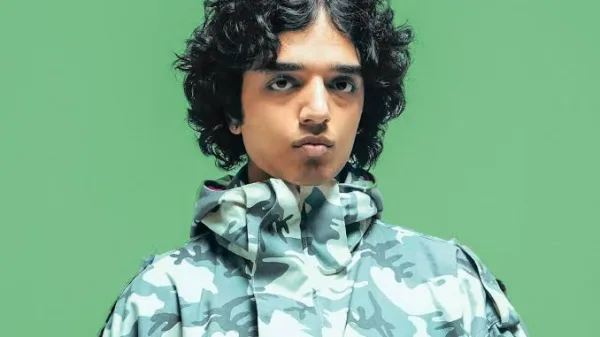

Whenever discourse about vulgarity and its place in the art we create and consume resurfaces in my life, I often think about Chekhov’s frustration with the ostentatious first-world connoisseurial elite who control and direct discussions in The Cherry Orchard, “What does exist is nothing but dirt, vulgarity, and a barbarian way of life… I dislike these terribly serious faces, they frighten me, and I’m afraid of serious conversations, too. We’d be better off if we all would just shut up for a while!” — It is unlikely that Anton Chekhov could have foreseen the rise of Gauntlet, the 19 year old rapper from Jaipur, who has been making waves utilizing profanity, lechery that is made to sound intentionally ludicrous, and the language of memes in the best/worst way possible.

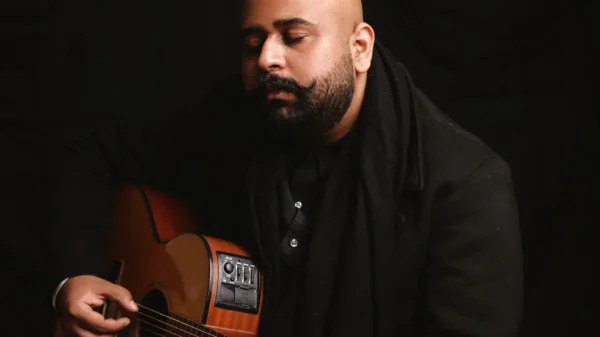

I had come across Gauntlet’s music the same way the rest of India’s chronically online population did : through the viral Mamta’s Interlude, that has amassed a whopping 16 million streams on Spotify, and birthed countless reels and multiple iterations of microtrends. Somehow, almost a year later, I also managed to see him perform live as one of the opening acts for a bigger rap collective in one semi-crowded Saket club — one of my first live desi hip-hop events, where I managed to perks of wallflower myself to a corner and observe the artist-crowd interaction, something that forms one of the cruxes of these performances. Gauntlet’s setlist consisted of tracks that do not actually count as his biggest hits — he did not take on Mamta’s Interlude, or his infamous Doraemon Diss — but instead his more niche collaborations with D0perman, who he shared the stage with. The rapper’s trademark autotuned, profane choruses delivered with the intentional cadence of self-aware ridicule caught on with the mostly deadened audience, becoming one of the more exciting performances of the night.

The rapper’s new EP TAALETODH TA**E (Super Deluxe) does not stray from his usual style. Sampling and parodying hall-of-fame Indian meme audios, like he does in MURGA MOBILE [Shani Kumar’s Murga Mobile Baate will always live on in public memory], interspersing mild commentary on the Delhi rap scene with audio-manipulated wretching noises in ASSIGNMENT 3, and returning with a second part to MAMTA’S INTERLUDE : he sticks to his devices and uses them better. Perhaps the most interesting track is LPG L*ND, which remaining in line with his own hyperpop influences, is very similar to 100 gecs’ iconic track money machine.

The essence of Gauntlet’s music is not new : India has had its own niche of “vulgar” music that spans centuries, and the pattern of social media stars using meme referentiality to make parody-esque spoof music is something that we saw in the days of CarryMinati and bbkivines. Perhaps the difference lies in the production — which is more Playboi Carti — Young Thug — Ken Carson driven, along with classic hyperpop influences, which is more in tune with the Gen-Z audience’s preferences.

One of the prime questions that bother critics when it comes to music like Gauntlet’s is whether to take it seriously, and sure, the rapper is not touching on a lot of subjects his contemporaries from desi hip-hop specific to the Delhi scene are broaching in their more elaborate, cohesive albums. However, what he, and many other creatives in the “meme-music” genre have managed to achieve is strike a chord with a huge section of the populace by drawing on the internet as a living, breathing cultural phenomenon, allowing it to directly seep into musical vocabulary. While this specific style of music-making might have an expiry date when it comes to its durability, Gauntlet and other artists in this specific niche are combining their artistry with a marked intent to not take things “too seriously”, mixed with perhaps the all too familiar Indian-middle-class urge to cuss out everyone and everything, and perhaps herein lies the always incomprehensible boundlessness of music.