In the sleepy village of Morjim in North Goa, not far from the tide-churned beaches that have long lost their charm to commercial noise, an old rice mill has been given a new life. One that doesn’t erase its history but tunes it to a different key.

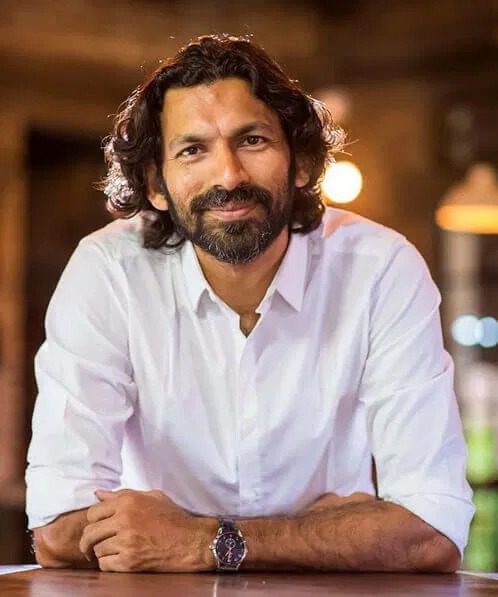

Architect Raya Shankhwalker, known for his deep sensitivity to place and memory, has transformed the abandoned structure into a jazz bar. The decision seems improbable at first glance — a rice mill and jazz, agriculture and improvisation, tradition and syncopation, but walk into The Rice Mill on any given evening, and it all begins to make sense.

Raya leased the neglected rice mill in a quiet village, intending nothing more than to preserve a piece of local heritage. Over time, within the restoration project, he created room for jazz to return too, restoring culture and music in one quiet, powerful gesture. Today, the mill stands at the heart of Goa’s jazz scene.

Every Saturday night, musicians gather here to improvise, perform, and reclaim a sound that once defined the state’s cultural identity. It’s a growing movement, where seasoned musicians return to their roots, and a new generation discovers and reclaims a genre that, for a time, was nearly forgotten.

The building doesn’t advertise itself. There is no loud signage, no marketing paraphernalia. Instead, you arrive at a low, quietly lit structure where the scent of aged wood mingles with the sharpness of citrus and smoke.

Inside, the architecture remains loyal to the mill’s original shape: sloping tiled roof, exposed beams, and pulley systems left intact not as decor but as testament. The bar is carved into the grain storeroom; the stage feels more hearth like than spotlight. It’s a place that feels less like a venue and more like a conversation between time and sound.

The music that fills the space is jazz, It is not an aesthetic choice but an act of reclamation, a gesture that connects the present not only to this specific structure’s past, but also to Goa’s largely forgotten relationship with jazz itself. Though now often associated with electronic music festivals, beach raves, and the peddling of curated ‘bohemian’ experiences, Goa was once one of India’s quiet epicenters of jazz, long before the word ever found its way into travel brochures or fusion playlists.

In the mid-20th century, Goan musicians were at the forefront of India’s thriving jazz scene, particularly in Bombay, which was a magnet for nightlife, cinema, and Western music. These musicians, many of them trained in church choirs, fluent in Western classical theory, and exposed to Portuguese influences in harmony and rhythm—brought an exceptional dexterity to the genre.

Figures like Chic Chocolate, the trumpet player known as “India’s Louis Armstrong,” or Anthony Gonsalves, the visionary arranger who blended Indian classical music with jazz harmonics, were central to the jazz age of Bombay. Sebastian D’Souza, another Goan maestro, was instrumental in shaping the orchestral arrangements that would define Hindi film music for decades.

These artists weren’t fringe experimenters; they were foundational. They played in the dance halls of Colaba, at the Taj and the Astoria, alongside visiting Americans and Europeans. They didn’t mimic jazz, they made it their own. Their compositions travelled through swing and bebop, often fusing seamlessly with Indian melodic sensibilities. Jazz in their hands was not a borrowed idiom; it was an elastic language that belonged to Bombay and, by extension, to Goa.

Jazz flourished in hotel lobbies and film studios, but not necessarily in the villages these musicians came from. That gap – the distance between the musician’s home and his audience, is what The Rice Mill quietly begins to close. It’s not just a bar that plays jazz. It’s a bar that makes jazz local again. In its architecture, its atmosphere, and its sound, it proposes a reversal of musical migration.

Raya Shankhwalker understood this deeply. His design is not just a restoration project, it is an acoustic and emotional composition. The space listens before it speaks. The building wasn’t stripped and modernised; it was invited to continue. The existing materials, brick, wood, rusted iron were kept and layered with care. There is a sense that the room remembers what it once held: sacks of rice, the heat of labour, the weight of repetition. Now it holds a different kind of rhythm, but one that resonates with the same integrity.

In an interview, Raya says that the key aspect of revival that is taking place is young Goan musicians taking to jazz music. “I think that is amazing. The legacy of the Goan jazz masters is being revived and taken ahead. The presence of a large number of international musicians that pass through Goa or live in Goa partly offers an amazing opportunity of collaboration and exposure.”

Shankhwalker’s passion for heritage began in college. He blends functional modernism with vernacular construction practices and firmly believes that all buildings do not simply need to be restored, but evolved. His commercial projects champion heritage as a catalyst for cultural revival.

Raya isn’t just an architect practicing in Goa. He’s Goan to the bone. His work is a testament to a place he loves fiercely, a place he’s watched transform at breakneck speed. In a time when heritage is too often flattened into façades or tourist-ready nostalgia, Raya’s approach is deeply rooted in care, continuity, and cultural truth.

He was subconsciously exposed to jazz through early Konkani tiatr music and Bollywood. “However all this was before I knew what jazz was. My first exposure to jazz was during my travels to Europe and its jazz bars. What drew me to jazz is its easy and relaxed character and its international spirit.” Perhaps it is this very spirit that beckoned him to revive what has been lost in Goa for so long.

The key aspect of revival that is taking place is young Goan musicians taking to jazz music and I think that is amazing. The legacy of the Goan jazz masters is being revived and taken ahead. The presence of a large number of international musicians that pass through Goa or live in Goa partly offers an amazing opportunity of collaboration and exposure,” he says.

Shankhwalker is clear about the others who have played a crucial role in the revival of jazz in Goa. “I would like to give due credit to Jonathan Furtado, a young bass player who has relentlessly promoted and supported Jazz in Goa. Jarryd Rodrigues who comes from a family of legendary Goan jazz musicians is another. Both Jarryd and Jonathan were instrumental in reviving jazz in Goa. The Samosa Trio, which is our most favourite jazz band, does amazing improvisations and makes jazz at our bar really fun,” he adds.

An overwhelming amount of the audience at The Rice Mill is under thirty. The visitors are also often international who want to explore the local jazz scene. What’s striking about The Rice Mill is the way it allows stillness to coexist with intensity. On some nights, the music is so delicate, the room so attuned, that every listener becomes a participant in the performance. Conversations soften into background murmurs, the scrape of a stool becomes part of the rhythm, and the clink of ice in a glass sounds percussive. On other nights, the energy builds and shudders and spills over. It is jazz the way it was meant to be experienced: up close, alive, unpolished, and generous.

The crowd that gathers here is as eclectic as the music. You’ll find retired Goan musicians, art school students from Baroda, Berlin-based pianists passing through, old hippies, new designers, and locals who remember when Morjim wasn’t a destination but just home. What thrives instead is presence, the kind that rarely survives in commodified nightlife. Each performance becomes a communal event, an offering that is never repeated and never archived, but somehow remembered.

Goa today is in a state of cultural flux. The pressures of tourism, real estate development, and demographic change have often pulled its identity in competing directions. Between the fetishisation of its colonial past and the appropriation of its landscape for profit, authentic Goan expression has struggled for visibility. What The Rice Mill manages, almost quietly, is to model a different way forward, one where heritage doesn’t have to be packaged or staged, but simply lived with honesty and care.

This is not a nostalgia project. Raya’s vision is not rooted in romanticising the past, but in making space for continuity. It is not about freezing a moment in time but about letting time fold into itself – so that a place which once produced food for the village can now nourish it differently, through sound, through gathering, through shared attention. The jazz played here is not a revival act. It is living music in a living space, grounded in history but not limited by it. That’s what Raya Shankhwalker has done at The Rice Mill. He has given Goa not a monument, but a movement. He has taken a forgotten structure and filled it with music that remembers.

It is hard not to think of La La Land. The bar leaves an ache in you of a fleeting strange beautiful sadness. If you visit, you will want to cling to it.